|

|

|

O moral Gower, this book I directe

To the and to the, philosophical Strode,

To vouchen sauf, ther nede is, to correcte,

Of youre benignites and zeles goode. |

Troilus and Criseyde (Book 5, l. 1856-1859)

Richard II was a great patron of the arts and a literary culture flourished

at his court in the second half of the Fourteenth Century. Chaucer was widely

known amongst the literati of the day, and his circle included influential

figures such as Sir Lewis Clifford, Sir Richard Stury and Sir John Montagu. He

was also friendly with other contemporary writers, including Thomas Hoccleve,

Henry Scogan, Ralph Strode and John Gower. He seems to have been particularly

close to ‘Moral’ Gower, as he dubs him in Troilus and Criseyde, giving him power

of attorney when he left for Italy in 1378. In the first version of his

Confessio Amantis, Gower makes a flattering reference to Chaucer as composing

‘ditees and songes glad’ in the flower of his youth.

Often referred to as the ‘Father of the English Language’ Chaucer’s poetry

and use of English inspired a whole generation of poets. The dominance of French

following the Norman conquest of 1066 had impeded the growth of English as a

literary language for hundreds of years, and it was not until the Fourteenth

Century that the vernacular came once more to be used as the language of choice

in all areas of society, including at court and in business. Nonetheless, most

writers – such as Gower – still wrote fluently in French and Latin, as well as

in their native tongue. Chaucer proved that English could be written with

elegance and power and it is thanks to his works that its prestige grew as a

medium for serious literature. His poetry naturally inspired praise and

imitation from his contemporaries. Of these admirers, the prolific John Lydgate

is probably one of the best known today. A monk at the great Benedictine Abbey

of St Edmund at Bury, he emulated Chaucer’s style, and in the prologue to his

Siege of Thebes even portrayed himself as meeting Chaucer’s pilgrims at their

inn in Canterbury. Although Lydgate’s work has suffered from adverse criticism

(the antiquarian Joseph Ritson famously dismissing him as a ‘voluminous,

prosaick, and drivelling monk’) he played a crucial role in ensuring Chaucer’s

popularity throughout the Fifteenth Century.

|

|

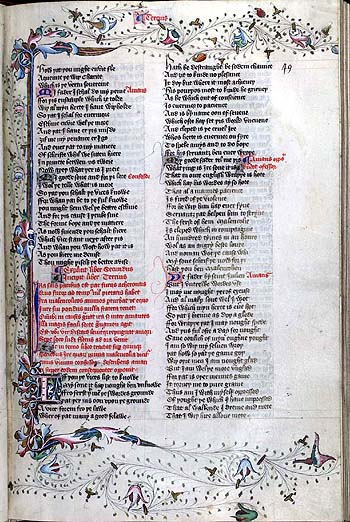

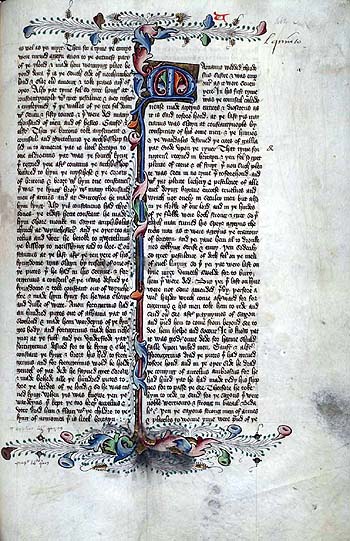

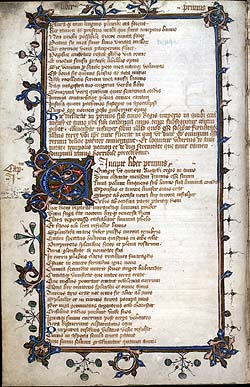

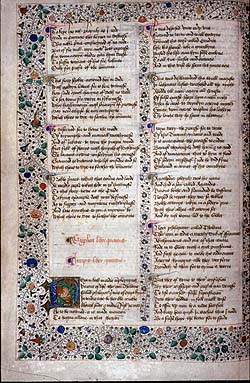

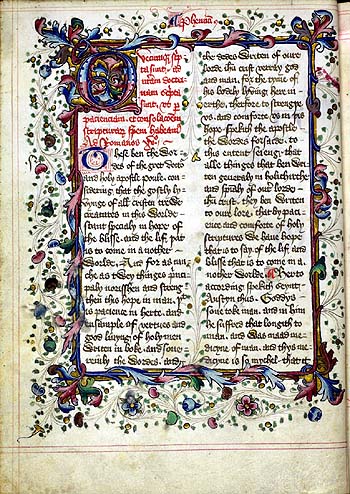

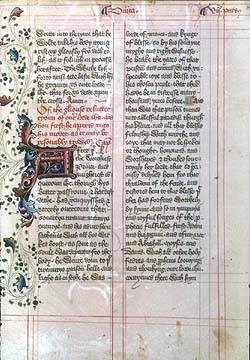

Illuminated page beginning Book 3 (folio 49r) |

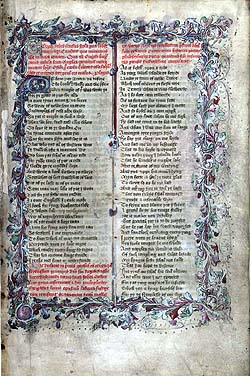

John Gower Confessio Amantis

England: c.1425-1450

MS Hunter 7 (S.1.7)The Confessio Amantis is Gower's most acclaimed English work. Completed in

its first version in 1390, when Gower was about sixty, it is a lover's account

of his confession to Genius, the priest of Venus, under headings supplied by the

seven deadly sins. Like The Canterbury Tales, Gower uses this narrative

framework to tell a series of tales which in this work explore the general

nature of each sin together with the particular forms it may take in a lover.

Chaucer undoubtedly knew the work well. According to the original prologue,

Gower wrote the book for Richard II after the king asked him for a poem on the

theme of love. Two or three years later, the reference to Richard was cut out,

presumably because of his growing unpopularity. Gower then wrote another version

of the prologue in which he says that the work was written for ‘Engelondes

sake’.

The decorative scheme in this manuscript was for the beginning of each book

to be marked by an illuminated and decorated page. The opening of the third book

is displayed to the left; it is adorned by a spraywork border incorporating floral and

leaf motifs. Several of these pages (including the beginnings of books one, two,

six, seven and eight) are missing, and this may suggest that they originally

included miniatures as well. There is a seventeenth century inscription in the

book indicating that it was owned by the Benedictine Abbey of Bury St Edmonds:

if this is correct, then this copy is likely to have been read by John Lydgate.

|

|

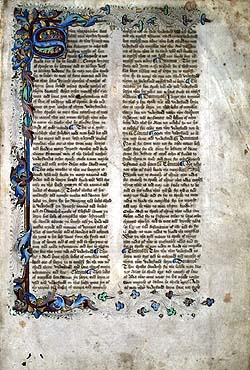

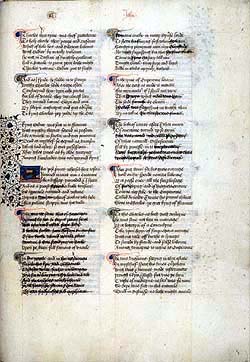

Illuminated page beginning text (folio 1r) |

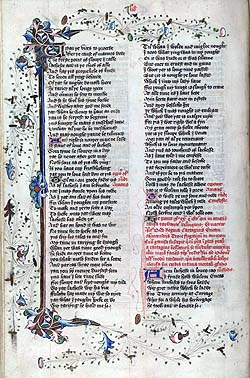

Illuminated page beginning book 4 (folio 65v) |

Illuminated page, ending Book 4 and beginning Book 5 (folio 87r) |

|

Illuminated page beginning Book 5 (folio 113r) |

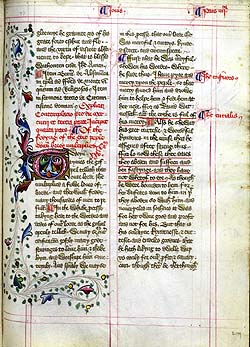

Ranulf Higden Polychronicon (translated by John of Trevisa)

England: c.1470

MS Hunter 367 (V.1.4)Originally composed in Latin, this universal history is a chronicle of the

period from the Creation to 1357. Its author was a Benedictine monk who arranged

the work into seven books, in imitation of the seven days of Genesis. This

translation was made by John of Trevisa (c.1330-1412) and completed in 1387.

There was an increasing interest in history throughout the late medieval period,

and Trevisa’s version was just one of several standard vernacular histories

available. His translation is interesting for the additional comments that he

makes to update the original text. Where Higden, for example, discusses the fact

that children learn their lessons in French, Trevisa comments that the

situation has changed by the time he is writing, and that lessons are now

conducted in English. He acknowledges that this has its advantages for speed of

learning, but points out rather disapprovingly that now children ‘know no more

French than their left heel, and that is harmful for them if they should pass

the sea and work in strange lands’.

This copy is one of some fourteen surviving manuscripts of the translation.

It also includes Higden's preface to the work, the Dialogue of the Lord and

the Clerk. The manuscript is well written on vellum and is skilfully decorated

with illuminated initials and floreated pages. To the left is the opening of the first

chapter of Book Five which deals with the reign of Vortigern in Britain and the

arrival of the Saxons Hengist and Horsa.

|

|

Illuminated page beginning text (folio 1r) |

Page with floreated initial 'T' (folio 200v) |

Illuminated page beginning book 2 (folio 34r) |

|

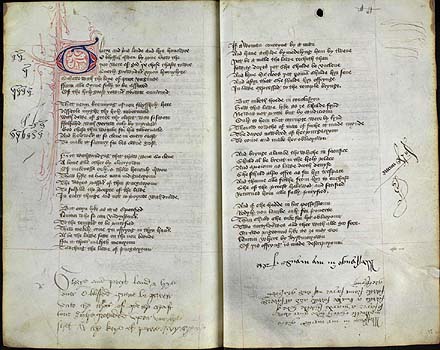

Portrait of Gower (folio 6v) |

John Gower Vox Clamantis

England: c.1400

MS Hunter 59 (T.2.17)Gower used the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 in this long Latin poem to describe

the faults of government and the various classes of society. Caused by a complex

interaction of social discontents, the Revolt was a brief but horrific episode

of anarchic insurrection. The rebels (not all of them peasants) plundered

London, massacred a group of Flemings, and murdered the Archbishop of

Canterbury. The earlier portion of the Vox Clamantis contains a vivid account of

this uprising in the form of an allegory, with a somewhat hysterical portrayal

of the rebels as domestic animals reverting to bestiality. Chaucer himself only

makes one passing reference to the Revolt in a facetious remark about Jack

Straw, one of its main leaders, in the Nun’s Priest’s Tale. Nonetheless, as a

member of the upper class, he probably shared Gower’s view of the rebels as

being a lawless rabble.

In this copy of the revised version of the Vox Clamantis and Chronica

Tripertita, the text is preceded by a full page representation of the author

firing his shafts at the world. This globe is composed of the elements of air,

earth and water in three compartments. There is a second illustration (found

towards the end of the text) of the Gower arms supported by two flying angels,

with a cloth-covered bier below. This does not depict Gower's coffin, as the manuscript was actually made before

his death in 1408. In fact, the text has been revised and corrected by means of

extensive erasure and substitution, possibly under the supervision of Gower

himself. There seems originally to have been another illustration on folio 131v,

but this has also been erased and only survives as a shadowy palimpsest beneath

the text.

|

|

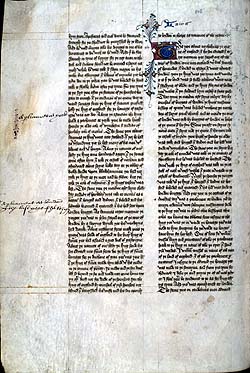

Decorated page beginning book 1 (folio 7v) |

Shield with Gower arms (folio 129r) |

Folio with palimpsest of illustration (folio 131v) |

|

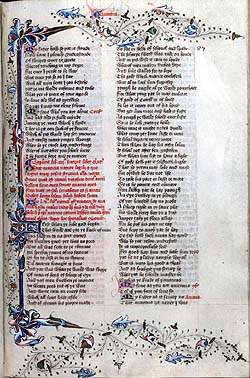

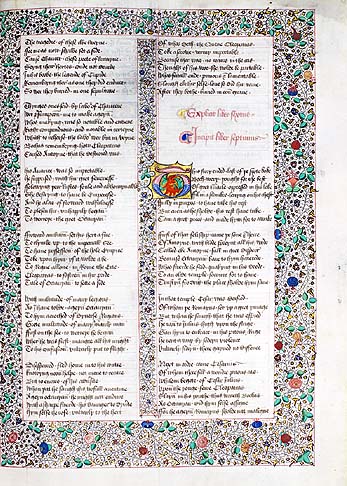

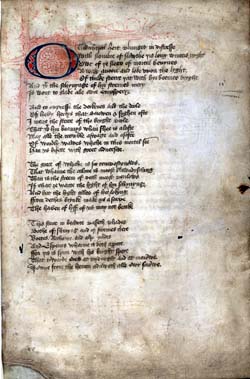

Illuminated page beginning Book 7 (folio 161r) |

John Lydgate Fall of Princes

England: c.1470-1480

MS Hunter 5 (S.1.5)Lydgate is credited with some 145,000 lines of verse, almost a quarter of

which is contained in the Fall of Princes, his longest single work. The poem is

a greatly amplified version of Laurent de Premierfait's translation of

Boccaccio's De Casibus Virorum Illustrium, with additions from a variety of

sources including the Bible, Ovid and other works by Boccaccio. The result is a

universal encyclopaedia of history and mythology, somewhat ponderous in tone and

exhaustively fleshed out with moral teaching. The work was commissioned from

Lydgate in 1431 by Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, younger brother of Henry V and

Protector of England during the minority of Henry VI, and it occupied the

following eight years of his life.

This is an imposing de-luxe copy of the work, written out in a very neat

hand. Its major decoration is found in six full page borders, filled with

delicate sprays of penwork in a foreign style. Like our copy of Gower's

Confessio Amantis, this copy is incomplete, the pages at the beginning of books

three and four having been cut out, probably for their decoration. One of the

quires has also been misbound, and several notes in an early seventeenth century

hand (including the instruction on one folio to 'Turne forwards eight leaves')

attempt to make this explicit to any reader. Another interesting feature is a

number of crossed out lines on folio 197r obliterating references to the female

'Pope Joan'. There are

several early ownership inscriptions at the end of the volume, including records

of the births of some members of the Lumner and Calthorpe families in the

Sixteenth Century.

|

|

Illuminated page beginning book 2 (folio 41r) |

Illuminated page ending book 4 and beginning book 5 (folio 125v) |

Illuminated page with crossing out (folio 197r) |

|

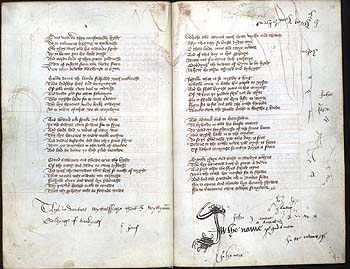

Opening with annotations (folios 99v-100r) |

John Lydgate Life of Our Lady

England: c.1450-1500

MS Hunter 232 (U.3.5)Lydgate wrote religious poetry throughout his career. The quasi-liturgical

Life of Our Lady was probably composed for Henry V in about 1415-16. A genuinely

devout composition written in the ‘high style’, the work draws upon the

Apocryphal Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, as well as other devotional texts such as

the Meditationes Vitae Christi. It has been praised for its religious intensity

and luminous rhetoric.

The manuscript is incomplete, missing the final part of the poem. It is a

fairly standard fifteenth-century production, well written with penwork initials

throughout, but lacking any illumination. It is interesting for its copious

early sixteenth-century marginalia. As well as numerous signatures, doodles and

pen trials, it bears fragments of administrative type annotations relating to

indentures, scraps of doggerel verse, and lines of quotations from the Gospels.

The opening on the left is typical: in the lower margin of the left hand page, the

beginning of the verse at the top of the page is repeated, while if the book is

turned upside down, a fragment of a poem may be read (‘Mussynge in my mynde

grete / mervell that I heve that ever / so fayer a mayde shoulde heve …’), along

with some practise letter ‘h’s and what might be a monogram. Many of the names

found in the margins are connected to the Goldings, an important Essex family of

the Tudor period.

|

|

Opening page (folio 1r) |

Opening with annotations (folios 57v - 58r) |

|

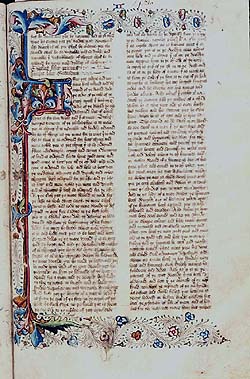

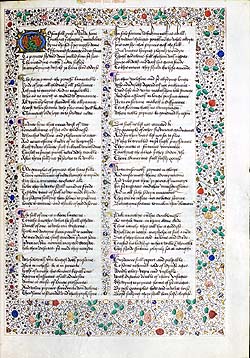

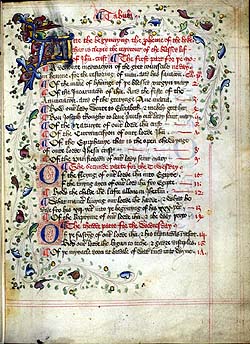

Illuminated page from the prologue (folio 3v) |

Nicholas Love Mirror of the Blessed Life of Jesus Christ

England: 1475

MS Hunter 77 (T.3.15)The Meditationes Vitae Christi, a devotional life of Christ originally

written in Latin, was extremely popular throughout medieval Europe. The Mirror

is a free translation of the work. It was made by Nicholas Love (d. 1424), a

prior of the Carthusian Priory of Mount Grace in Yorkshire. Concentrating on the

Passion, the Mirror dispenses meditative and doctrinal comment on the Bible. Its

sixty three chapters are each split into seven sections, every section

representing a day of the week.

This is a finely produced manuscript written in an expert script on good

quality vellum. It boasts several floreated pages, with illuminated initials and

decorative penwork throughout. Stephen Dodesham (d. 1481/82), its scribe, is

identified from a contemporary inscription on a flyleaf. He was a monk of Witham

Charterhouse near Frome, Somerset; he later moved to Sheen Charterhouse in

Richmond, Surrey, founded by Henry V in 1414. Dodesham was a prolific scribe

whose career began in the late 1420s; over twenty of his manuscripts survive,

including two others in the Hunterian collection.

|

|

Table of contents (folio

1r) |

Decorated page ending book 3 and beginning book 4 (folio 76r) |

Decorated page ending part 6 and beginning part 7 (folio 133r) |

|

|