Impact of intentional weight loss in cardiometabolic disease: what we know about timing of benefits on differing outcomes

Naveed Sattar, John Deanfield, Christian Delles

Introduction

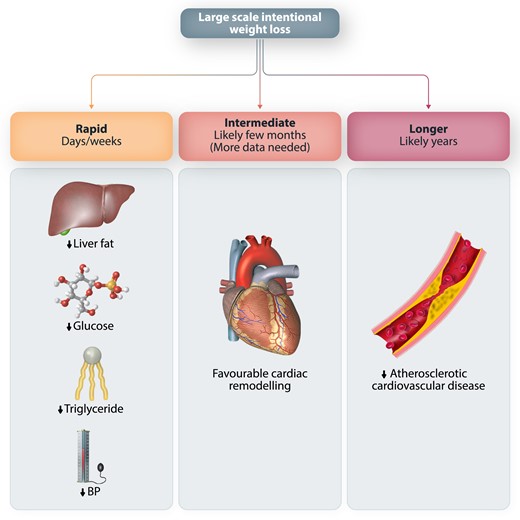

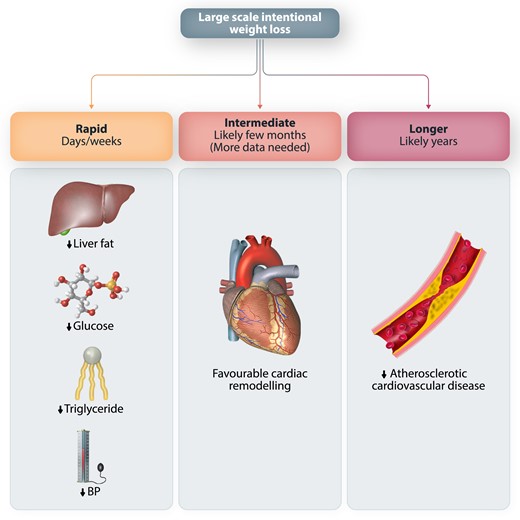

There is a widening appreciation that excess adiposity may be a more important risk factor for multiple cardiometabolic outcomes than previously imagined. Gains in knowledge from well-conducted epidemiological studies, genetics, and follow-ups of bariatric surgery studies have stimulated more interest in the role of intentional weight loss in preventing or treating cardiometabolic disease. However, it is less well appreciated that the timing of such benefits may vary dependent on the disease process considered (Figure 1). Such issues are important as the results of several outcome trials (e.g. SELECT,1 SURPASS-CVOT2) testing the benefits and safety of agents that cause considerable weight loss, often 10 kg or more, will report over the next several years.3,4 As the relevant drugs also likely deliver direct tissue benefits, the pattern and timing of any outcome benefits in these trials will be eagerly scrutinized to try to decipher the relative contributions of direct drug effects vs. impacts of their large-scale weight loss.

Rapid effect (within days or weeks)—glycaemia and related (ectopic fat, lipid) pathways

One of the most rapid changes following intentional weight loss is improvements in glycaemia. We see this in numerous trials where the pattern of weight loss often precisely mirrors the pattern of change in HbA1c in patients with Type 2 diabetes.5 This close association now makes sense as the pathogenesis of Type 2 diabetes has become clearer; rapid weight loss begets prompt reductions in liver fat and circulating triglycerides levels, in turn reflecting reductions in ectopic fat.6,7 The consequence is rapid improvements in liver insulin sensitivity (leading to better control of gluconeogenesis) and, potentially a slightly slower improvement in beta cell function, the latter via reduction in fat in islet cells.7 In line with this, the seminal DiRECT trial reported rapid benefits of a low-calorie diet on liver fat, triglyceride levels, and glycaemic indices, with many patients undergoing diabetes remission.

Rapid effects (within weeks)—blood pressure reduction

Low-calorie diets lead to rapid (within few weeks) reductions in systolic blood pressure in people with recently onset Type 2 diabetes, including those who stopped their antihypertensive medications.11 Other trials with other agents also see rapid reductions in blood pressure with weight loss.12 The timing of the changes is sufficiently fast as to suggest haemodynamic changes may be operating, perhaps in part via reductions in sodium intake. To what extent reductions in perivascular fat or other mechanisms contribute to short or long term reductions in blood pressure require further elaboration. Clearly, more research on mechanisms linking intentional weight loss to reductions in blood pressure is needed, including the impact of intentional weight loss in those with resistant hypertension.

Final thoughts

For years, the medical profession has been hesitant to place too much effort in helping people lose weight or prevent weight gain in the first place. However, the rise in worldwide adiposity levels has resulted in considerable comorbidity that is hugely affecting clinical care in all specialities.24 Furthermore, new tools, both lifestyle and drugs, that aid meaningful weight loss now offer the potential to better trial and understand links between excess adiposity and cardiometabolic outcomes. Such work should extend to cardiorenal outcomes and should, importantly, examine the timing and mechanisms for any observed changes. We hope our brief review of relevant evidence explains how and why differing outcomes will likely improve at different times after weight loss and how such changes may be inter-related. This review should also serve as a call for more mechanistic studies in relevant areas.

First published: 25 January 2023