BIOGRAPHIES OF OBJECTS

Introduction

Among the varied collections of The Hunterian, there are numerous objects made by Indigenous Peoples from around the world, including items from what is now called North America. These objects tell stories of contact between Scottish people and First Peoples in North America, about the Scottish travelling to other countries, about First Peoples travelling to Scotland, and about objects travelling from one country to the other as gifts, souvenirs, or forcibly taken goods. The Hunterian online catalogue provides us with information regarding the objects’ materials and their possible geographical origins. However, it does not give us any information about their makers or how they arrived in Scotland. The catalogue leaves the following questions unanswered:

- Who made the objects and why?

- How did they come the long way from North America to Scotland?

For some objects, but not all, we know who donated them and little else. Without the factual biographies of these objects, we have to rely on other sources to understand their stories. It is possible that the objects travelled to Scotland with Indigenous diplomats, missionaries, activists, performers, or other visitors. Throughout the centuries, Native Americans from the USA as well as First Nation, Inuit and Métis peoples from Canada came to Scotland. This exhibition seeks to give voice to these objects to tell those stories.

Acknowledgements and Credits

We would like to thank the Huron-Wendat Museum, in Wendake, Quebec, Canada, for their collaboration with this project.

to thank the Huron-Wendat Museum, in Wendake, Quebec, Canada, for their collaboration with this project.

We would also like to thank Jonathan Lainey (Wendat), McCord Museum, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, for his support.

We are very grateful to Dr Renae Watchman (Diné/Tsalagi) for sharing with us her knowledge on Diné rugs.

We would like to credit Élodie Langella for her support with the French translation.

Native Americans and First Peoples of Canada in Scotland

Indigenous North American Women and Children in Scotland

Native Americans and Canadian First Peoples have visited Britain, either voluntarily or forcibly, since the 16th century. In the 19th century Scotland became home for some Indigenous people from North America, when former Scottish employees from the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) returned to Scotland with Indigenous partners and their children.

The Hudson’s Bay Company and the Scottish connection

The Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) was chartered in 1670 and had its headquarters in London. The HBC is the oldest merchandising company in the anglophone world. Originally, it was involved in the fur trading. The history of the HBC is closely entangled with the history of colonization of British North America, specifically of what we nowadays call Canada. The royal charter gave the HBC extensive powers over a large territory. This territory was called Rupert’s Land. It contained a third of what is now Canada. Nowadays, the HBC still exists and includes several hundred department stores.

Many people from Scotland participated in one way or another in the endeavour of British imperialism abroad. The colonies were places where Scottish people could make or remake their fortunes. The HBC and Scotland were also closely connected. For instance, at the end of the 18th century, Orkney men constituted ¾ of the HBC labour force. In subsequent years, Orkney was an important place to source more labour force for the HBC.

In Rupert’s Land, HBC men marrying Indigenous women became part of extensive Indigenous kinship, trading, political and legal networks. Likewise, through their marriages to British men, Indigenous women became part of British imperial networks.

Scotland: Old Home and New Home

At the end of their service, some HBC men returned home to Scotland. They brought their wives and children with them back to Scotland. For example, the family of the HBC’s chief trader, called Chief Factor, John Ballenden settled in Edinburgh. The family of Chief Trader Donald Sutherland moved to Clyne. The family of Nicol Finlayson and the family of Chief Factor Angus Cameron lived Nairn. Chief Factor George Keith and his wife Ann Sutherland (1788 - 1862) settled in Aberdeen. Further families lived in Orkney or the Shetlands.

Sometimes, the Indigenous-Scottish families did not return to Scotland but stayed in Canada. In some cases, however, they sent their children, often boys, to Scotland to attend school and university here. The children then lived with their Scottish relatives. Some of the children later returned to Canada when working for the HBC as adults. The children’s book Carry My Bones Northwest (1973), by W. Towrie Cutt tells the story of an Indigenous child sent to Scotland to attend school. Other children stayed in Britain. They made careers here, married and had children of their own. Nowadays, descendants of Indigenous-Scottish families can be found all over the world, from Canada to Scotland to Australia.

Some HBC wives were of Indigenous and European ancestry, thus having their own family connections to Britain. For instance, Ellen Matthews Barnston (1815 - 1893) had an English father and a Chinook mother . Elizabeth Kennedy (1808-1842) had Scottish and Cree parents. Margaret McKenzie was the daughter of the Scot Roderick Mackenzie and his Ojibwe wife Angelique.

The children of Scottish HBC men and Indigenous women often grew up with their mother’s native languages. Those, who did not speak the local English before coming to Britain, learned it after settling in Scotland. In some cases, women and children had to learn Gaelic as well, for example, when settling in Orkney or the Isle of Lewis. Scottish HBC husbands are known to have practiced their Indigenous language skills with their colleagues after their return to Scotland. Others wrote in English, Gaelic, French and Cree, or other Indigenous languages letters to their loved ones in Britain and in North America.

After moving to Scotland, some families tried to re-create some features of their life in Canada. For instance, they grew plants from Canada in their Scottish gardens. Donald Alexander Smith, Lord Strathcona, planted a forest on his new estate in Glencoe for his wife Isabella Sophia Hardisty (1825-1913), Lady Strathcona, using trees from Rupert’s Land. Similarly, Chief Factor Angus Cameron planted tree seeds from Rupert’s Land when settling in Nairn.

John Norton Teyoninhokarawen

John Norton was a diplomat, interpreter and translator, writer, soldier and trader. He was born on December 16, 1770, in Dunfermline, Scotland. His father was Cherokee and his mother Scottish. Norton went to school in Scotland, in Dunfermline and in Edinburgh. Later on, he joined the British army through which he came to Canada in 1785. After being discharged from the army, Norton worked in the USA and in Canada.

John Norton was a diplomat, interpreter and translator, writer, soldier and trader. He was born on December 16, 1770, in Dunfermline, Scotland. His father was Cherokee and his mother Scottish. Norton went to school in Scotland, in Dunfermline and in Edinburgh. Later on, he joined the British army through which he came to Canada in 1785. After being discharged from the army, Norton worked in the USA and in Canada.

Norton became acquainted with the famous Mohawk chief Thayendanegea (John Brant) in the 1790s. Eventually, Norton was adopted as a Mohawk of the Six Nations Council. The Council named Norton Teyoninhokarawen. This name has the meaning ‘it keeps the door open’. In 1805, Teyoninhokarawen (Norton) travelled to Britain as a diplomat on the Mohawks’ behalf to negotiate full title to Mohawk land. Unfortunately, his diplomatic mission was not a success and he returned to Canada.

Teyoninhokarawen came to Scotland for another visit in 1815. He returned for a year with his young wife, Karighwaycagh (Catherine) and one of his sons, Tehonakaraa (John Norton jun.) They both attended school in Dunfermline in Scotland. A year later, Teyoninhokarawen returned to Canada with his family. He died presumably in 1831 in North Mexico.

Image:

Teyoninhokarawen (Major John Norton), ca. 1805, Oil on canvas, Mather Brown, (1761 - 1831). © Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund, B2010.5.

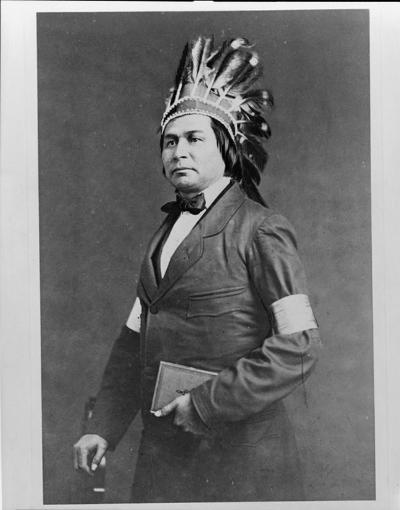

Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh (George Copway)

Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh was born in 1818 in Ontario and died in 1869 in Quebec. He was a Mississauga (Ojibwa) and worked as a translator, Methodist minister, lecturer and writer. He lived and worked in Canada and the USA.

Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh was born in 1818 in Ontario and died in 1869 in Quebec. He was a Mississauga (Ojibwa) and worked as a translator, Methodist minister, lecturer and writer. He lived and worked in Canada and the USA.

In 1850, Copway travelled through Europe. He also visited Scotland. Following his trip to Europe, he published his third book, Running Sketches of Men and Places, in England, France, Germany, Belgium, and Scotland. He died in 1869.

Image:

Marian S. Carson Collection. Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh – G. Copway, ca. 1860. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

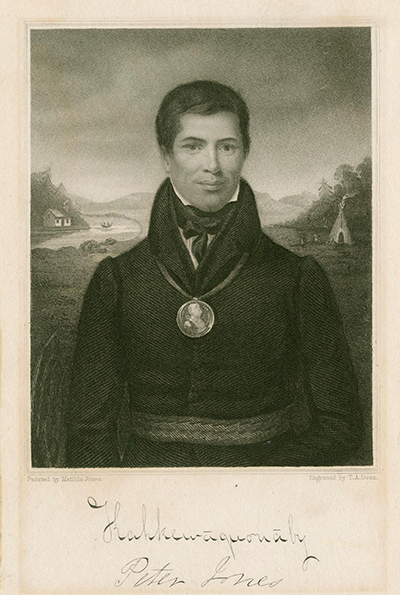

Kahkewaquonaby (Peter Jones)

Kahkewaquonaby was a Mississauga Ojibwa Chief. He was born in 1802 in Hamilton in Canada and died 1856 near Brantfort in Canada. He worked as a Methodist minister, author, translator and a farmer. His name means ‘sacred feathers’ or ‘sacred waving feathers’. His father was born in Wales and later immigrated to America. His mother was Tuhbenahneequay (Sarah Henry), the daughter of a Mississauga chief. Because of his stepmother, Kahkewaquonaby was adopted into her Mohawk tribe. He was given the Mohawk name Desagondensta which means ‘he stands on his feet’. While attending school, Kahkewaquonaby was given the name Peter Jones.

Kahkewaquonaby was a Mississauga Ojibwa Chief. He was born in 1802 in Hamilton in Canada and died 1856 near Brantfort in Canada. He worked as a Methodist minister, author, translator and a farmer. His name means ‘sacred feathers’ or ‘sacred waving feathers’. His father was born in Wales and later immigrated to America. His mother was Tuhbenahneequay (Sarah Henry), the daughter of a Mississauga chief. Because of his stepmother, Kahkewaquonaby was adopted into her Mohawk tribe. He was given the Mohawk name Desagondensta which means ‘he stands on his feet’. While attending school, Kahkewaquonaby was given the name Peter Jones.

As part of his missionary work, he travelled to Britain where he gave speeches and sermons and collected money for the Methodist missionary work. During his third missionary tour in Britain in 1845, Kahkewaquonaby also travelled to Scotland. A series of photographs were shot during his stay in Scotland. These pictures are held by the Scottish National Portrait Gallery and can be viewed online. His health began to fail in the 1840s and eventually Kahkewaquonaby died in 1855 following his final illness.

Image:

Kahkewaquonaby, Peter Jones (1832), Acc. No: OHQ-PICTURES-S-R-967 © Courtesy of Toronto Public Library.

The Huron- Wendat

The Huron-Wendat is a First Nation now living in Wendake, near Quebec City, in Canada.

The Huron-Wendat is a First Nation now living in Wendake, near Quebec City, in Canada.

The Huron-Wendat and Souvenir Art

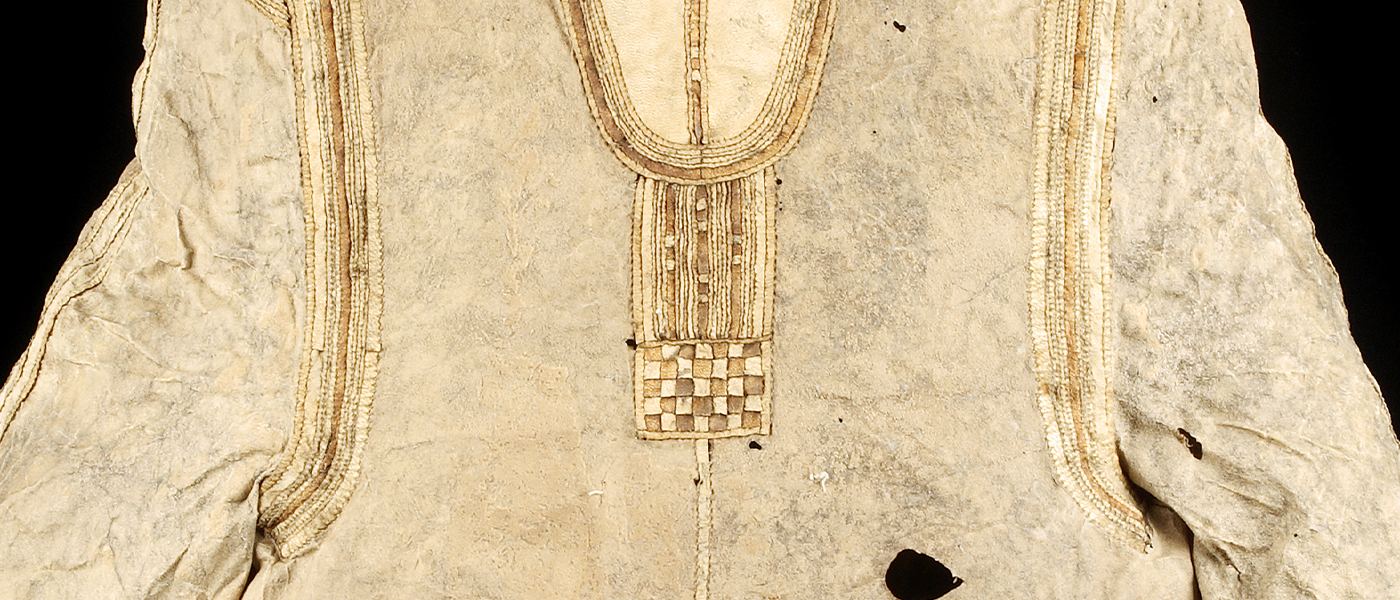

The Huron-Wendat produced souvenir art for European tourists from the late 18th to the late 19th century. The Huron-Wendat women were famous for their souvenir art. For example, they embroidered deer skin with dyed moose hair and porcupine quill. They were successful entrepreneurs. They sold their products across North America. Some families travelled to New York or Toronto for the summer to sell their wares at popular tourist resorts.

Two successful women artists were Marguerite Vincent La8inonkie (left of image) and Caroline Gros-Louis (right of image). Works from both La8inonkie and Gros-Louis can be found in museums and collections around the world.

In the past, Lorette, where the Huron-Wendat live, was a popular tourist destination where tourists purchased souvenir art.  Among the many visitors to Lorette were the British statesman and his wife Lord and Lady Elgin. Lord Elgin was the Governor General of Canada from 1847 to 1854. During their visits, they acquired several pieces of Huron-Wendat souvenir art, some of which they probably brought back to Britain. Further visitors to Lorette and buyers of souvenir art also included Scottish tourists and soldiers. It is possible that some of the Scottish visitors to Lorette brought back Huron-Wendat souvenirs to Scotland.

Among the many visitors to Lorette were the British statesman and his wife Lord and Lady Elgin. Lord Elgin was the Governor General of Canada from 1847 to 1854. During their visits, they acquired several pieces of Huron-Wendat souvenir art, some of which they probably brought back to Britain. Further visitors to Lorette and buyers of souvenir art also included Scottish tourists and soldiers. It is possible that some of the Scottish visitors to Lorette brought back Huron-Wendat souvenirs to Scotland.

The Hunterian unfortunately has no record of who produced the mittens (GLAHM:E.105) and mocasins (GLAHM:E.111) shown here, or indeed how they came to Scotland. However, they are thought to be examples of souvenir art which was produced for European tourists from the late 18th to late 19th centuries. Maybe they were brought to Scotland by Huron-Wendat visitors or by Scottish tourists who had visited Lorette.

The Huron-Wendat in Britain

Huron-Wendat diplomats also visited Britain. In 1825, four representatives of the Huron-Wendat travelled to England. Grand Chief Nicolas Vincent Tsawenhohi, Chief Michel Tsiouï Teachaendale, Chief Stanislas Coska Aharathala and Chief Andre Romain Tsohahissan came to meet King George IV. They brought with them gifts to the king and to others they met along the way. Maybe some of their gifts found their way up North to Scotland.

After spending several months in Britain, the Huron-Wendat chiefs returned to Lorette. They brought home the gifts they had received, for instance, gifts from the king and items of clothing. These items were adopted into the Huron-Wendat clothing style. The Huron-Wendat women decorated these new items with fine moose hair embroidery.

Images from the top:

Images from the top:

Top left: Madame Paul Ricard, née Marguerite Vincent. (Marguerite Vincent La8inonkie),Ludger Ruelland, Musée de la civilisation;Top right: Caroline Gros-Louis, Ethnographic Museum Stockholm.

GLAHM.E.105, Mittens, and GLAHM.E.111 Children’s moccasins, probably from the Huron-Wendat © The Hunterian.

Nicholas Vincent Tsawenhohi, by Edward Chatfield (1802-1839). 1825. Print. McCord Museum. M20855. CC BY-NC-ND 2.5 CA.

Les Hurons-Wendats (Français)

Biographies des objets. Histoires des objets autochtones d’Amérique du Nord.

Introduction

Les collections diverses du musée Hunterian contiennent des objets créés par des peuples autochtones autour du monde, incluant des objets de l’Amérique du Nord. Ces objets racontent beaucoup d’histoires différentes. Des histoires entre des Écossais et des peuples autochtones autour du monde. Des histoires des Écossais qui ont voyagé d’un pays à un autre. Des histoires des autochtones qui ont voyagé en Écosse. Des histoires des objets qui ont voyagé d’un pays à un autre comme cadeaux, souvenirs ou comme des objets qui étaient pris violemment.

Le catalogue numérique du musée Hunterian nous donne des informations concernant les matériaux des objets et leurs origines géographiques possibles. Par contre, il ne nous donne aucune information concernant leurs creáteurs.trices ou comment ils sont arrivés en Écosse. Le catalogue ne répond pas aux questions suivantes :

- Qui a fait les objets et pour quelle occasion ?

- Comment sont-ils venus d’Amérique du Nord en Écosse ?

Il y a des objets dont nous connaissons le nom du donateur ou de la donatrice. Sans connaître les vraies biographies des objets, nous utilisons d’autres ressources pour comprendre leurs histoires. Il est possible que ces objets aient voyagé avec des diplomates, missionnaires, performeurs et militant.e.s ou d’autres visiteur.se.s autochtones en Écosse. À travers les siècles, des autochtones des États-Unis et du Canada sont venus en Écosse. En utilisant des sources autochtones d’Amérique du Nord, cette exposition essaie de donner une voix aux objets pour raconter leurs histoires ou des histoires des visteur.se.s autochtones en Écosse.

Les Hurons-Wendats

Les Hurons-Wendats

Les Hurons-Wendats sont une Première Nation habitant à Wendake, près de la ville Québec, au Canada.

L’artisanat chez les Hurons-Wendats

Les Hurons-Wendats ont produit des objets utilitaires pour les touristes européennes de la fin du 18e à la fin du 19e siècle. Les femmes huronnes-wendat étaient connues et célébrées pour leur artisanat des objets souvenirs. Par exemple, elles ont brodé de la peau de cerf avec du poil d’orignal teinté et des piquants de porc-épic. Elles étaient des entrepreneuses très efficaces. Elles ont vendu leurs objets souvenirs partout en Amérique du Nord. Il y avait des familles qui sont allées à New York ou Toronto l’été pour vendre leurs objets souvenirs aux villes touristiques populaires.

Deux artistes très connues sont Marguerite Vincent La8inonkie et Caroline Gros-Louis. Des objets créés par La8inonkie et Gros-Louis se trouvent aujourd’hui partout dans le monde, dans divers musées et collections.

Dans le passé, Lorette, s’appelant aujourd’hui Wendake, la ville de la Nation huronne-wendat, était également une ville touristique populaire. Beaucoup de visiteur.se.s y sont allé.e.s pour acheter des objets souvenirs. Parmi ces touristes à Lorette, il y avait également Lord et Lady Elgin. Lord Elgin était le gouverneur général du Canada entre 1847 et 1854. Pendant leurs visites, ils ont acheté plusieurs objets souvenirs des Hurons-Wendats. Ensuite, plusieurs de ces objets sont venus en Grande-Bretagne. De plus, des touristes et des militaires écossais sont également venus à Lorette pour y acheter des objets souvenirs. Ainsi, il est possible que quelques visiteurs de Lorette soient revenus en Écosse avec des objets créés par des Hurons-Wendats.

Dans le passé, Lorette, s’appelant aujourd’hui Wendake, la ville de la Nation huronne-wendat, était également une ville touristique populaire. Beaucoup de visiteur.se.s y sont allé.e.s pour acheter des objets souvenirs. Parmi ces touristes à Lorette, il y avait également Lord et Lady Elgin. Lord Elgin était le gouverneur général du Canada entre 1847 et 1854. Pendant leurs visites, ils ont acheté plusieurs objets souvenirs des Hurons-Wendats. Ensuite, plusieurs de ces objets sont venus en Grande-Bretagne. De plus, des touristes et des militaires écossais sont également venus à Lorette pour y acheter des objets souvenirs. Ainsi, il est possible que quelques visiteurs de Lorette soient revenus en Écosse avec des objets créés par des Hurons-Wendats.

Malheureusement, le musée Hunterian n’a aucune information concernant les creáteurs.trices les gants (GLAHM :E.105) et les mocassins (GLAHM :E.111), présentés ici, ou comment ils sont arrivés en Écosse. Par contre, nous pensons qu’ils sont des souvenirs qui étaient produits pour les touristes européens entre la fin du 18e et la fin du 19e siècle. Ces souvenirs étaient peut-être amené en Écosse par des visiteurs wendats ou par des touristes écossais qui avaient visité Lorette.

Les Hurons-Wendats en Grande-Bretagne

Les Hurons-Wendats ont eux-mêmes visité la Grande-Bretagne. En 1825, quatre représentants de la Nation huronne-wendat se sont rendus en Angleterre. Grand Chef Nicolas Vincent Tsawenhohi, Chef Michel Tsiouï Teachaendale, Chef Stanislas Coska Aharathala et Chef Andre Romain Tsohahissan étaient venus pour rencontrer le roi George IV. Étant en visite officielle entre deux nations indépendantes, ils ont amené des cadeaux avec eux pour le roi britannique. Il est possible que quelques objets hurons-wendats aient quitté l’Angleterre et soient venus en Écosse.

Après avoir passé plusieurs mois en Grande-Bretagne, les chefs des Hurons-Wendats sont revenus à Lorette. Plusieurs objets sont revenus avec eux en Amérique du Nord, par exemple des cadeaux royaux et plusieurs objets et vêtements. Ces objets ont été adoptés et incorporés dans le style vestimentaire des Hurons-Wendats. Les femmes huronnes-wendat ont décoré ces nouveaux objets avec la broderie au poil d’orignal.

Après avoir passé plusieurs mois en Grande-Bretagne, les chefs des Hurons-Wendats sont revenus à Lorette. Plusieurs objets sont revenus avec eux en Amérique du Nord, par exemple des cadeaux royaux et plusieurs objets et vêtements. Ces objets ont été adoptés et incorporés dans le style vestimentaire des Hurons-Wendats. Les femmes huronnes-wendat ont décoré ces nouveaux objets avec la broderie au poil d’orignal.

Images du haut:

En haut à gauche: Madame Paul Ricard, née Marguerite Vincent. (Marguerite Vincent La8inonkie), Ludger Ruelland, Musée de la civilisation.

En haut à droite: Caroline Gros-Louis, Ethnographic Museum Stockholm.

GLAHM.E.105, Mittens, and GLAHM:E.111 moccasins enfants, probablement créés par Huron-Wendat © The Hunterian.

Nicholas Vincent Tsawenhohi, Edward Chatfield (1802-1839). 1825. McCord Museum. M20855. CC BY-NC-ND 2.5 CA.

Inuit

Perfectly Adapted to Survival in the Arctic

Inuit are an Indigenous group from the Arctic. The word ‘Inuit’ means ‘the people’ in Inuktitut, the Inuit language. Before Inuit settled in permanent locations, they travelled seasonally and lived off the land. Inuit live from what the Arctic has to offer. For example, animals are used for food, clothing, fuel and tools. Every part of the animal is used, nothing is wasted. Animal furs are made into clothes. In the past, sinew was turned in to sewing yarn and bones into needles, bows and arrows. Different types of equipment were used to hunt different animals. Hunting is still an important activity for Inuit. Today, Inuit hunters combine modern equipment and machinery with traditional hunting. Country food includes all the essential nutrients for a healthy diet in the Arctic. It can consist of seal, caribou, fish, or berries.

Inuit are an Indigenous group from the Arctic. The word ‘Inuit’ means ‘the people’ in Inuktitut, the Inuit language. Before Inuit settled in permanent locations, they travelled seasonally and lived off the land. Inuit live from what the Arctic has to offer. For example, animals are used for food, clothing, fuel and tools. Every part of the animal is used, nothing is wasted. Animal furs are made into clothes. In the past, sinew was turned in to sewing yarn and bones into needles, bows and arrows. Different types of equipment were used to hunt different animals. Hunting is still an important activity for Inuit. Today, Inuit hunters combine modern equipment and machinery with traditional hunting. Country food includes all the essential nutrients for a healthy diet in the Arctic. It can consist of seal, caribou, fish, or berries.

The right clothing is essential for the survival in the Arctic. Traditionally, Inuit clothing includes a parka, trousers, mittens and several layers of footwear. Caribou furs or seal skin were used to make clothing. Depending on the season, Inuit wore one or two layers. When wearing two layers in the winter, the first coat had the fur turned inwards. The second coat wore the fur on the outside. In this way, heat was kept inside and the coldness outside. The air trapped inside the two coats functioned as insulation. Caribou furs are particularly suited for warm clothes.  Caribou hair is hollow inside. Thus, it traps air and works excellently as an insulation against the cold. Seals have compact and flat hair that repels water. Seal skin and seal furs are excellently suited for wet conditions. Nowadays, Inuit still make traditional clothing. They incorporate modern materials. Traditional Inuit clothing is more efficient to keep its wearer warm and dry than southern fabricated clothing.

Caribou hair is hollow inside. Thus, it traps air and works excellently as an insulation against the cold. Seals have compact and flat hair that repels water. Seal skin and seal furs are excellently suited for wet conditions. Nowadays, Inuit still make traditional clothing. They incorporate modern materials. Traditional Inuit clothing is more efficient to keep its wearer warm and dry than southern fabricated clothing.

Images:

GLAHM:E.372/2, knife. A knife made of bone and GLAHM:E.104, cagoul, Inuit, North America.

GLAHM:E.1984.5/2, sealskin mittens and GLAHM:E.1984.5/1, sealskin parka Frobisher Bay, Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada.

The Tlingit

In their own language, they call themselves Lingít which means ‘people of the tides’. In English, they are called Tlingit. Since time immemorial they have lived in the Pacific Northwest in what is nowadays British Columbia, Yukon and Alaska. Their traditional territories were located along the coast as well as inland. The rainforest in the Pacific Northwest as well as the coastal areas provided the Lingít with abundant resources to support themselves throughout the year. Beside fishing, they also hunted land mammals and birds. In addition, they were able to trade products with other peoples across vast trading networks. The biennial festival Celebration in Juneau, Alaska, showcases traditional song and dance, arts and crafts and local languages. The festival celebrates the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian cultures.

In their own language, they call themselves Lingít which means ‘people of the tides’. In English, they are called Tlingit. Since time immemorial they have lived in the Pacific Northwest in what is nowadays British Columbia, Yukon and Alaska. Their traditional territories were located along the coast as well as inland. The rainforest in the Pacific Northwest as well as the coastal areas provided the Lingít with abundant resources to support themselves throughout the year. Beside fishing, they also hunted land mammals and birds. In addition, they were able to trade products with other peoples across vast trading networks. The biennial festival Celebration in Juneau, Alaska, showcases traditional song and dance, arts and crafts and local languages. The festival celebrates the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian cultures.

Image:

GLAHM:E.1983.46, engraving tool probably from the Tlingit, British Columbia, Canada, © The Hunterian.

The Diné (Navajo)

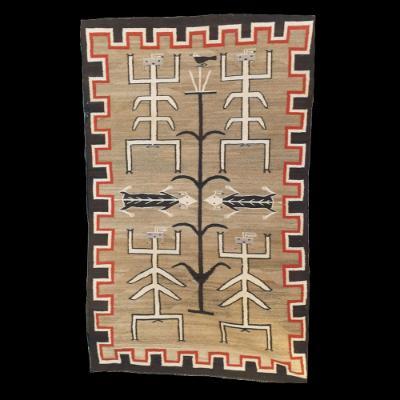

The word Diné means The People in the Navajo language. The Navajo homeland, also called Dinétah or Diné Bikéyah, spans over three states: Utah, Arizona and New Mexico. The Hunterian holds two Navajo rugs in its collection. In fact, the Navajos are well known for their rugs. Na’ashjé’ii ‘Asdzáá (Spider Woman) taught the Diné the art of weaving. For many generations they have been accomplished weavers and continue to be so today. The knowledge of weaving is passed down from one generation to the next.

The word Diné means The People in the Navajo language. The Navajo homeland, also called Dinétah or Diné Bikéyah, spans over three states: Utah, Arizona and New Mexico. The Hunterian holds two Navajo rugs in its collection. In fact, the Navajos are well known for their rugs. Na’ashjé’ii ‘Asdzáá (Spider Woman) taught the Diné the art of weaving. For many generations they have been accomplished weavers and continue to be so today. The knowledge of weaving is passed down from one generation to the next.

The Diné were part of extensive trading networks. They traded, for example, with people from Mexico to receive specific dyed yarns. They also traded their rugs with other First Peoples to receive various utilitarian goods. In addition, they traded with the Spanish and Anglo-Americans. Depending on the market and the tastes of their trading partners, Diné weavers created new patterns to respond to the market.

Despite the weaver’s essential role in the weaving of rugs, they are basically absent from historical records. Indeed, the Hunterian catalogue only notes the name of the donor of the rug (Ms Jos Marlowe) but gives no indication of the weaver of the rug. At the moment, we do not know where and when the weaver made the rug. Neither do we know why they chose this specific pattern. Did they work alone or were they surrounded by their family, their children? When did they work on the rugs? How did they feel when weaving? How long did it take them to finish this rug? The catalogue currently leaves these questions unanswered.

We are grateful to Dr Renae Watchman (Diné/Tsalagi) for this explanation of the pattern of the rug pictured. As the artist of this rug is unknown, Dr Watchman’s explanation is only one interpretation.

"In the middle of the picture, a corn stalk is depicted with a bird atop. The figures in the corners are the ye'iis (Holy People). Their presence in the pattern means that the pattern depicts a ceremony in the corn stalk teachings. The bird atop the corn stalk could mean a number of things. It is possible that it refers to the Blue Bird Song, which is the final song after the Shiprock Yeiibichei dances."

Image:

GLAHM:112367, rug, USA, Diné (Navajo). © The Hunterian.

Biographies of Objects Online Collection

View our Online Collection grouped and curated for Biographies of Objects.

Project Origins - Hunterian Associates Programme

This project originated through the Hunterian Associates Programme.

Find out more via the Biographies of Objects Project Page.

Bibliography

Indigenous Women and Children in Scotland

Barclay, Krista. 2019. ‘“Far asunder there are those to whom my name is music”: Nineteenth-Century Hudson’s Bay Company Families in the British Imperial World’, unpublished doctoral thesis (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba).

Brown, Alison K., Christina Massan and Alison Grant. 2011. ‘Christina Massan's Beadwork and the Recovery of a Fur Trade Family History’, in Recollecting. Lives of Aboriginal Women of the Canadian Northwest and Borderlands, ed. by Sarah Carter and Patricia A. McCormack (Edmonton: AU Press): 89-111.

McCormack, Patricia A. 2013. ‘Transatlantic Rhythms: To the Far Nor'Wast and Back Again’, in Irish and Scottish Encounters with Indigenous Peoples: Canada, the United States, New Zealand, and Australia, ed. by Graeme Morton and David A. Wilson (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press): 253-286.

McCormack, Patricia A. 2011. ‘Lost Women: Native Wives in Orkney and Lewis’, in Recollecting. Lives of Aboriginal Women of the Canadian Northwest and Borderlands, ed. by Sarah Carter and Patricia A. McCormack (Edmonton: AU Press): 61-88.

Wilson, Bryce. 2008. ‘Hands across the sea: Orkney and the Hudson’s Bay Company’, in Material Histories. Proceedings of a workshop held at Marischal Museum, University of Aberdeen, 26-27 April 2007, ed. by Alison K. Brown (Aberdeen: Marischal Museum, University of Aberdeen): 21-28.

John Norton / Teyoninhokarawen

Davis, D.S. 2013. ‘John Norton (Teyoninhokarawen)’, The Canadian Encylopedia, <https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/john-norton-teyoninhokarawen> [accessed 29 September 2021].

Fulford, Tim. 2006. ‘John Norton/Teyoninhokarawen’, in Romantic Indians. Native Americans, British Literature, and Transatlantic Culture 1756-1830 (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press): 211-223.

Klinck, Carl F. 1987. ‘Norton, John (Snipe, Teyoninhokarawen)’, Dictionary of Canadian Biography, 6 (University of Toronto / Université Laval), <http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/norton_john_6E.html> [accessed 29 September 2021].

Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh (George Copway)

Fulford, Tim. 2006. ‘Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh / George Copway’, in Romantic Indians. Native Americans, British Literature, and Transatlantic Culture 1756-1830 (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press): 280-291.

Smith, Donald B. [1976] 2015. ‘Kahgegagahbowh (Kahkakakahbowh, Kakikekapo) (George Copway)’, Dictionary of Canadian Biography, 9 (University of Toronto / Université Laval), <http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kahgegagahbowh_9E.html> [accessed 30 September 2021].

Smith, Donald B. 2013. ‘George Copway (Kahgegagahbowh)’, The Canadian Encyclopedia, <https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/george-copway> [accessed 30 September 2021].

Kahkewaquonaby (Peter Jones)

Adamson, Robert and David Octavius Hill. 1843-1847. ‘Rev. Peter Jones or Kahkewaquonaby, 1802-1856. Indian chief and missionary in Canada’. Photograph. Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Elliot Collection, bequeathed 1950. Accession number: PGP HA 1205, <https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/66775/rev-peter-jones-or-kahkewaquonaby-1802-1856-indian-chief-and-missionary-canada-g> [accessed 29 September 2021].

Fulford, Tim. 2006. ‘Peter Jones / Kah-Ke-Wa-Quo-Na-By’, in Romantic Indians. Native Americans, British Literature, and Transatlantic Culture 1756-1830 (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press): 255-263.

Smith, Donald B. 1987. Sacred Feathers. The Reverend Peter Jones (Kahkewaquonaby) & the Mississauga Indians (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press)

Smith, Donald B. 1985. ‘Jones, Peter’, Dictionary of Canadian Biography, 8 (University of Toronto / Université Laval), <http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/jones_peter_8E.html> [accessed 29 September 2021].

The Wendat

Beaulieu, Alain, Stéphanie Béreau, and Jean Tanguay. 2013. Les Wendats du Québec. Territoire, économie et identité, 1650-1930 (Québec: Les Éditions Gid).

Marginean, Denisa. 2020. ‘Crafting an Artistic Identity in the Late-Nineteenth Century: Caroline Gros-Louis’, Yiara Magazine [accessed 22 January 2021].

Tanguay, Jean. 2012. ‘Marguerite Vinvent La8inonkie: « la femme habile aux travaux d’aiguille »’, in Représentation, métissage et pouvoir. La dynamique coloniale des échanges entre Autochtones, Européens et Canadiens (XVIe-XXe siècle), ed. by Alain Beaulieu and Stéphanie Chaffray (Québec : Presses de l’Université Laval): 447-474.

Phillips, Ruth B. 1999. ‘Nuns, Ladies, and the “Queen of the Huron”. Appropriating the Savage in Nineteenth-Century Tourist Art’, in Unpacking Culture. Art and Commodity in Colonial and Postcolonial Worlds, ed. by Ruth B. Phillips and Christopher B. Steiner (Berkeley: University of California Press): 33-50.

Sioui, Georges E. 1999. Huron-Wendat. The Heritage of the Circle, transl. by Jane Brierley, rev. edn. (Vancouver: UBC Press).

Sioui, Linda. 2007. ‘The Huron-Wendat Craft Industry from the 19th Century to Today’, McCord Museum [accessed 30 October 2020].

Sioui, Linda. 2008. ‘The Huron-Wendat Craft Industry from the 19th Century to Today’, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nZUgWu-0fyc [accessed 30 October 2020].

Stecher, Anne de. 2009. ‘Huron-Wendat Historical Visual Arts Tradition: Symbol of Cultural Continuity and Autonomy in the Past, Source of Inspiration in the Present’, St Andrews Journal of Arts History and Museum Studies, 13: 87-94.

Stecher, Anne de. 2014. ‘Les arts wendats au service de la diplomatie et de la traite’, Recherches amérindiennes au Québec, 44.2-3: 65-77.

Stecher, Anne de. 2015. ‘Of Chiefs and Kings. Wendat and British diplomatic traditions, 1838-1842’, Ethnologies, 37.2: 103-130.

Phillips, Ruth B. 1998. Trading Identities. The Souvenir in Native North American Art from the Northeast, 1700-1900 (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press).

‘Your candidates for the next $5 bank note’, https://www.bankofcanada.ca/banknotes/banknoteable-5/nominees/ [accessed 22 January 2021]

Stecher, Anne de. 2015. ‘Of Chiefs and Kings. Wendat and British diplomatic traditions, 1838-1842’, Ethnologies, 37.2: 103-130.

Chatfield, Edward. 1825. ‘Nicholas Vincent Tsawenhohi’, McCord Museum, http://collections.musee-mccord.qc.ca/en/collection/artifacts/M20855 [accessed 22 January 2021]

Chatfield, Edward. 1825. ‘Michel Tsioui / Stanislas Coska / Andre Romain’, Library and Archives Canada, https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=fonandcol&IdNumber=3030877&new=-8585902888865399434 [accessed 22 January 2021]

‘Tsawenahohi, Ignace-Nicolas Vincent, National Historic Person’, Parks Canada, https://www.pc.gc.ca/apps/dfhd/page_nhs_eng.aspx?id=1941 [accessed 22 January 2021].

Sioui, Georges E./Atsistahonra. 1988. ‘Vincent, Nicolas’, Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 (University of Toronto/Université Laval), http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/vincent_nicolas_7E.html [accessed 22 January 2021]

Inuit

Compton, Richard. 2019. ‘Inuktitut’, The Canadian Encylcopedia, <https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/inuktitut> [accessed 19 April 2021].

Freeman, Minnie Aodla. 2020. ‘Inuit’, The Canadian Encyclopedia, <https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/inuit> [accessed 19 April 2021].

‘About Canadian Inuit’, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, <https://www.itk.ca/about-canadian-inuit/> [accessed 19 April 2021].

Kikkert, Peter. 2020. ‘Nunavut’, The Canadian Encyclopedia, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/nunavut [accessed 19 April 2021].

McGhee, Robert. 2013. ‘Inuvialuit’, The Canadian Encyclopedia, <https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/mackenzie-inuit> [accessed 19 Aril 2021].

‘Nunavut’, The Canadian Encylopedia, <https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/timeline/nunavut> [accessed 19 April 2021].

Rivet, France. 2020. ‘Nunavik’, The Canadian Encyclopedia, <https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/nunavik> [accessed 19 April 2021].

‘Parka and trousers’, McCord Museum, ME966X.127.1-2.

‘Young girl’s parka’, McCord Museum, ME967X.43, <http://collections.musee-mccord.qc.ca/en/collection/artifacts/ME967X.43> [accessed 19 April 2021].

‘Bow’, McCord Museum, M13053, <http://collections.musee-mccord.qc.ca/en/collection/artifacts/M13053> [accessed 19 April 2021].

Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada. Revised 2006. The Inuit Way. A Guide to Inuit Culture, <inuuqatigiit.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/inuitway_e-Pauktutit.pdf> [accessed 19 April 2021].

Vowel, Chelsea. 2016. Indigenous Writes. A Guide to First Nations, Métis and Inuit Issues in Canada (Winnipeg: Highwater Press)

Younging, Gregory. 2018. Elements of Indigenous Style. A Guide for Writing by and about Indigenous Peoples (Edmonton: Brush Education)

The Tlingít

‘Celebration’, Sealaska Heritage, https://www.sealaskaheritage.org/institute/celebration [accessed 12 October 2021]

‘Eyak, Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian’, Alaska Humanities Forum [accessed 4 October 2021]

‘Fishing and Hunting’, American Museum of Natural History [accessed 12 October 2021]

Hollinger, Eric and Nick Partridge. 2017. ‘3D Technology May Revive this Ancient Hunting Tool’, Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/blogs/national-museum-of-natural-history/2017/10/25/3d-technology-may-revive-ancient-hunting-tool/ [accessed 12 October 2021]

McClellan, Catharine. 2019. ‘Tlingit’, The Canadian Encyclopedia, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/inland-tlingit , [accessed 12 October 2021]

‘The Tlingit People Today’, The Louis Shotridge Digital Archive, https://www.penn.museum/collections/shotridge/the_tlingit.html [accessed 4 October 2021]

‘Tlingit’, American Museum of Natural History [accessed 12 October 2021]

‘Tlingit Fishing’, Haines Sheldon Museum, https://www.sheldonmuseum.org/vignette/tlingit-fishing/[accessed 12 October 2021]

Worl, Rosita. ‘Tlingit’, Alaska Native Collections, Smithsonian Institute, https://alaska.si.edu/culture_tlingit.asp [accessed 12 October 2021]

The Diné (Navajo)

Amador, Cihuapilli Rose and Teocauhtli Sundust Martinez. 2014. ‘Anecita Agustinez (Navajo/Dine), Navajo Rugs’, Native Voice TV, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fAFSHjd_6tA

Barney, Lyndzey, Whitney Harlos and Skylar Ogren. 2013. ‘Nita Nez. Navajo Rug Weaver’, The Navajo Oral History Project. A Collaborative Project of Diné College and Winona State University. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=La-y8p4GGKk

Craft in America. 2016. ‘Navajo weavers Barbara Teller Ornelas and Lynda Teller Pete’, Craft in America, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=axGeXfOPU84

Denetdale, Jennifer Nez. 2007. Reclaiming Diné History. The Legacies of Navajo Chief Manuelito and Juanita (Tucson: University of Arizona Press).

Hedlund, Ann Lane. 2004. Navajo Weaving in the Late Twentieth Century. Kin, Community, and Collectors (Tucson: University of Arizona Press).

Kent, Kate Peck. 2002. Navajo Weaving: Three Centuries of Changes (Santa Fe, N.M.: School of American Research Press).

Lilly, Grace and Florence Riggs. 2021. ‘History Behind the Arts. Interview with Cultural Demonstrator Florence Riggs. Diné Textile Weaver’, Grand Canyon National Park Service, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SPLJ0UWg2A4

M’Closkey, Kathy. 2002. Swept Under the Rug. A Hidden History of Navajo Weaving (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press).

Silversmith, Shondiin. 2013. ‘Rugs of the People. Weavers get behind-the-scenes glimpse at museum’s collection’, Navajo Times, 27 November 2013, https://navajotimes.com/entertainment/culture/2013/1113/112713rugs.php.

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. 2017. ‘“Hear My Voice”. Artist Profile: D.Y. Begay’, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v9wmz5rf1NU

Webster, Laurie D. 2017. ‘Changing Markets for Navajo Weaving’, in Navajo. The Crane Collection at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, ed. by Laurie D. Webster, Louise I. Stiver, D.Y. Begay, and Lynda Teller Pete (Colorado: Denver Museum of Nature and Science): 49-77.