Energy in History exhibition

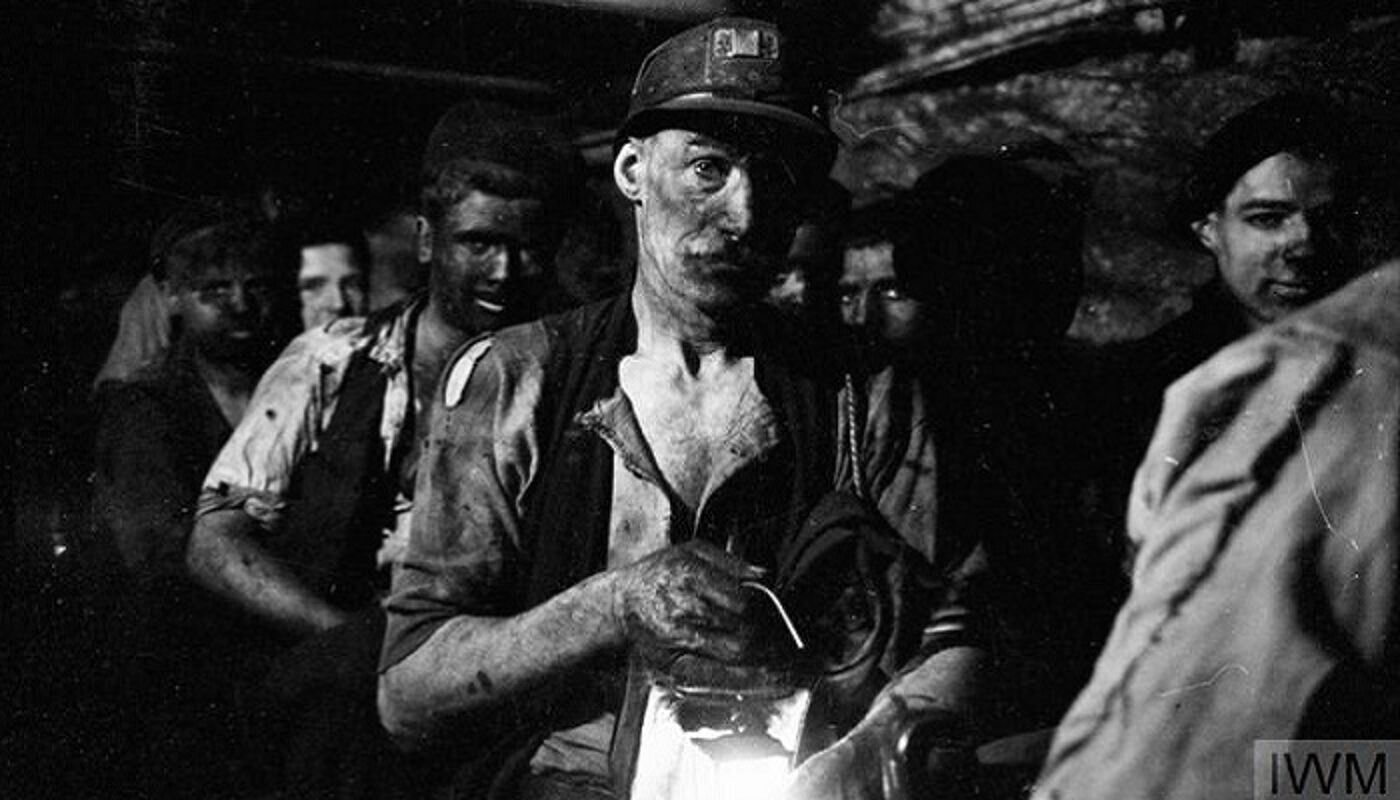

Follow the story of energy through the experiences of workers, local communities and citizens.

This online exhibition takes you from the dominance of coal to the oil boom and then the expansion of nuclear power and renewables.

Navigating Energy History course

Join our online course to learn more about Britain's historical energy transitions and their impact on today's sustainable energy challenges.

The Energy That Made Modern Scotland podcast

Historian Dr Ewan Gibbs and sociologist and writer Dr Dominic Hinde bring alive the story of North Sea energy through archive clips, expert interviews and academic analysis.

More resources

Key publication from the research, articles, blogs and podcasts, plus more resources on energy ownership and Scotland's response to climate change.

About Energy in History

More about the research projects behind the Energy in History website and the people who created the materials.