Zoology 1923 - 1935

The new building with its modern facilities opened in the autumn/winter of 1923 – lecture classes commenced there on the 8th October despite no seating yet installed in the lecture theatre. New regulations on the awarding of B. Sc Honours degrees came into force in 1924, and there was a modest increase in the number of zoology students alongside the large numbers of medics. Further staff were recruited including the following:

Dr Margaret Wolfe Jepps MA, D.Sc. (1892 – 1977)

Margaret Jepps, a distinguished protozoologist, worked in the Zoology Dept for almost 30 years (1923 – 1952). Like Sister Monica Taylor, her research interests lay mainly in amoebae, but specifically those parasitic species of medical importance; in 1918, along with Clifford Dobell, she described a new parasite of the human gut, Dientamoeba fragilis, commonly found worldwide, which may cause clinical symptoms including abdominal pain and diarrhoea. The exact nature of this organism is still being researched today. Just after WW1, she worked on amoebic dysentery in Malaysia. Jepps published widely on Protozoa (and occasionally on other organisms – sponges, parasitic worms). In retirement, in 1956, she produced a textbook, ‘The Protozoa: Sarcodina’ based on her lectures to undergraduates at Glasgow and intended as a general introduction to these organisms.

George Stuart Carter FRSE FLS FZS (1893 – 1969)

Carter was appointed to a lectureship in 1923 and undertook general teaching duties. He worked at the University Marine Station at Millport on the Isle of Cumbrae and produced a series of papers on reproduction in echinoderms. In 1926 -27 , he followed in Graham Kerr’s footsteps and led an expedition back to the Paraguayan Chaco, later he made other field trips to South America and Uganda; he was a keen evolutionist, deeply interested in the adaptive pressures on animals living in tropical swamps and published several papers on this subject. He left Glasgow in 1930 to take up a post at Cambridge University. In his later career he wrote a number of influential textbooks on evolution as well as a popular undergraduate text ‘General Zoology of Invertebrates’ (1940) which ran to four editions over the following 20 years.

Miss Agnes E. Miller BSc PhD

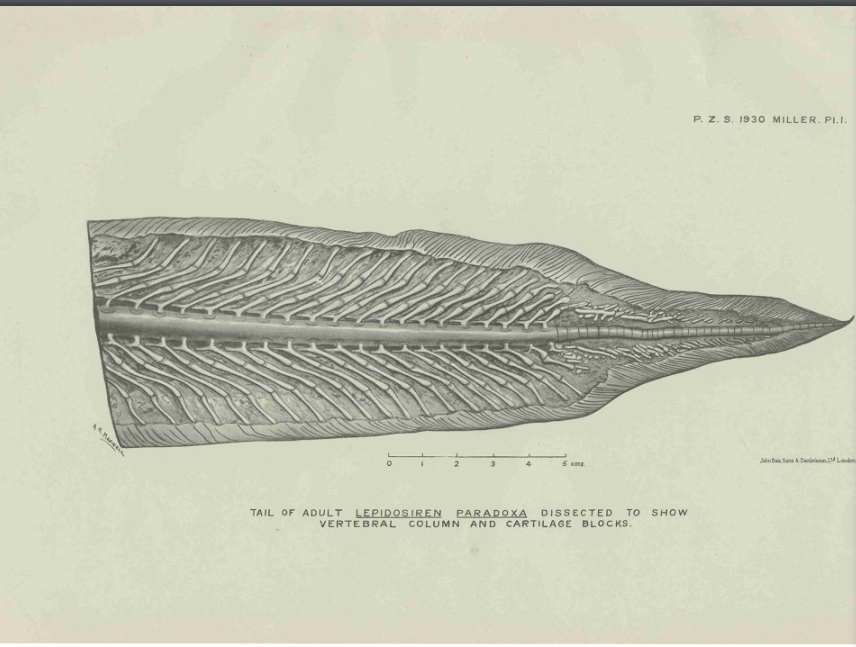

Agnes ‘Nora’ Miller was a student in the zoology class in 1917 and subsequently joined the staff in 1924 as a demonstrator, subsequently lecturer. She had a long career in the Zoology Department retiring in 1963. Influenced by Graham Kerr’s interest in the evolution and origins of early vertebrates, she undertook research into the morphology of the lungfish and the nature and phylogeny of the enigmatic fish-like fossil, Palaeospondylus, specimens of which had been found in the famous Achanarras slate quarry in Caithness, Scotland. The affinities of Palaeospondylus have been a puzzle since its discovery in 1890. Millers’ work suggested it was more closely related to lungfish rather than lampreys as previously thought: studies in 2022 using SRXTM scanning confirm its position in the stem lineage of the tetrapods.

Miller’s paper in the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London on lungfish tail structure and Palaeospndylus

Credit: ©University of Glasgow

Plate from PZS paper of dissection showing fine detail of Lepidosiren lungfish tail structure

Credit: ©University of Glasgow

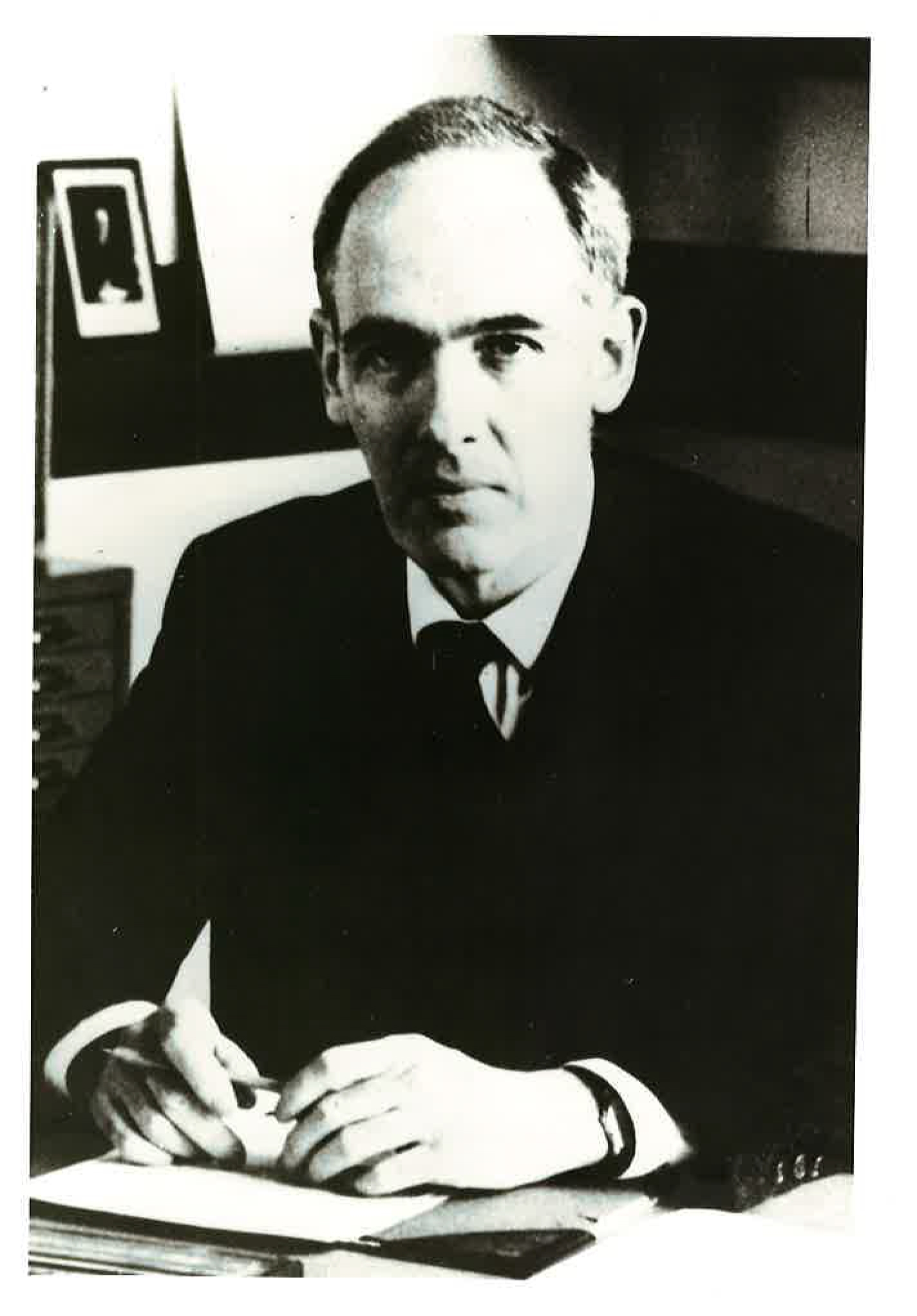

Charles Wynford Parsons FRSE 1901 – 1950

Charles Wynford Parsons, a zoologist from Cambridge University, was appointed to an assistant lectureship in 1926. In Glasgow, Parsons research interests were in vertebrate morphology focussing on studies on fishes and the embryology of birds. Looking to elucidate evolutionary links between birds and reptiles and in the then accepted belief that emperor penguins were especially primitive birds, he worked on the emperor penguin eggs and embryos collected on two of the famous British expeditions to Antarctica – the successful Discovery Expedition of 1901 and the disastrous Terra Nova expedition of 1910, both led by Robert Falcon Scott. In appalling conditions, the Terra Nova expedition members Henry Bowers, Bill Wilson and Apsley Cherry-Garrod collected three eggs containing developing embryos. Bowers and Wilson died along with Scott. Apsley Cherry-Garrod, though badly damaged, survived and brought the preserved eggs back – he presented them to the Natural History Museum in London and pressured experts to study them as the eggs had been collected at very great human cost. Richard Assheton at Cambridge and James Cossar Ewart at Edinburgh University both worked on the eggs and in 1934 the NMH asked Parsons continue the studies. Sadly though considering the effort to obtain them, Parsons concluded that ‘they did not greatly add to our understanding of penguin embryology’ but he remained proud that he had been able to complete this work. Outwith his research career, Parsons was a popular teacher (in charge the medical classes) and a capable administrator, involved in running the Department especially in the WW2 years, sitting on University committees and participating in various University and related academic activities. He died suddenly in 1950.

Charles W. Parsons, lecturer in Zoology, 1926 – 1950

Credit: ©University of Glasgow

Hugh Bamford Cott D. Sc (1900 – 1987)

Hugh Cott was appointed to a lectureship at Glasgow in 1933. Initially trained as a soldier at Sandhurst , he then studied zoology at Cambridge and in the 1920s participated in field trips to South America and Africa which inspired his interests in animal form, adaptive coloration and camouflage. He was talented artist and photographer and his pen and ink drawings, and black and white photographs of animals are outstanding. In Glasgow, under Graham Kerr’s supervision he completed a research degree, awarded as a D.Sc. in 1938, on adaptive coloration in the Anura (frogs). He shared Graham Kerr’s passionate interest in developing military camouflage based on a thorough understanding of the adaptive principles of animal camouflage (though both men had limited success in influencing official policy on camouflage). Cott served as a camouflage instructor and expert for three years after WW1 and for the duration of WW2. His classic work ‘Adaptive Colouration in Animals’ published in 1940 remains a core text on this subject today. Cott left Glasgow to serve again and after the war returned to Cambridge University where he worked until his retirement in 1967.

Regius Chairs in Natural History, then Zoology:

- Lockhart Muirhead MA LLD (1807)

- William Couper MA MD (1829)

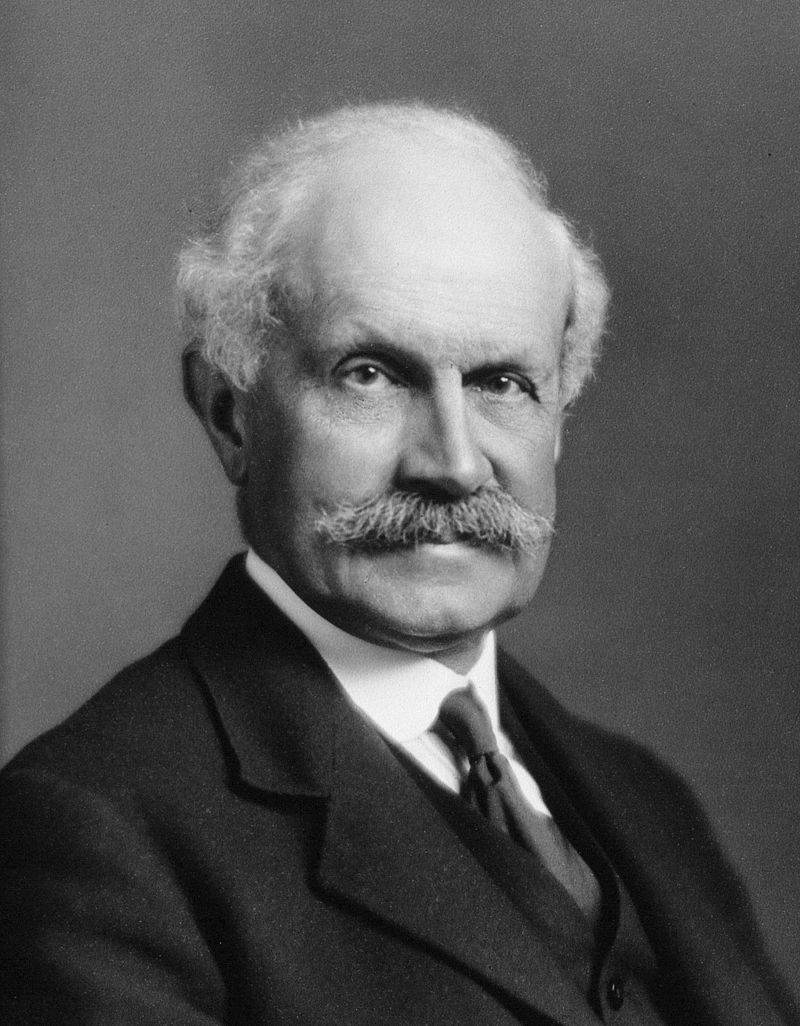

- Henry Darwin Rogers MA LLD (1857)

Source: Popular Science Monthly Volume 50

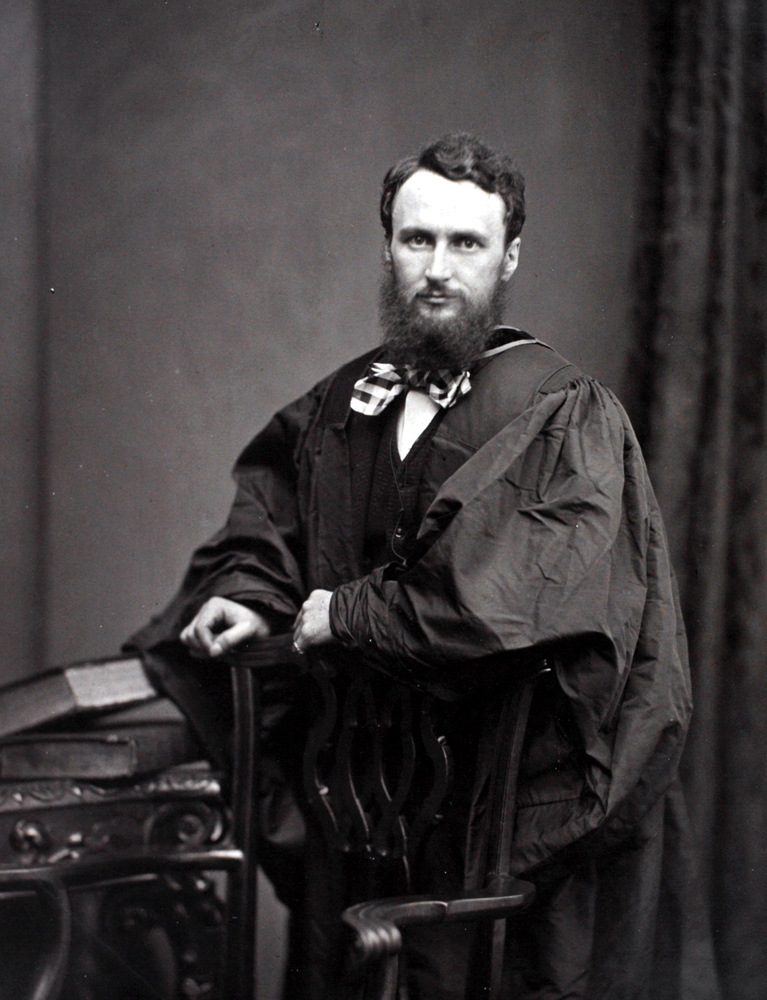

- John Young MD (1866)

Credit: ©University of Glasgow

- Sir John Graham Kerr MA LLD FRS (August 1902)

Credit: ©University of Glasgow

- Edward Hindle MA PhD ScD FRS (1935)

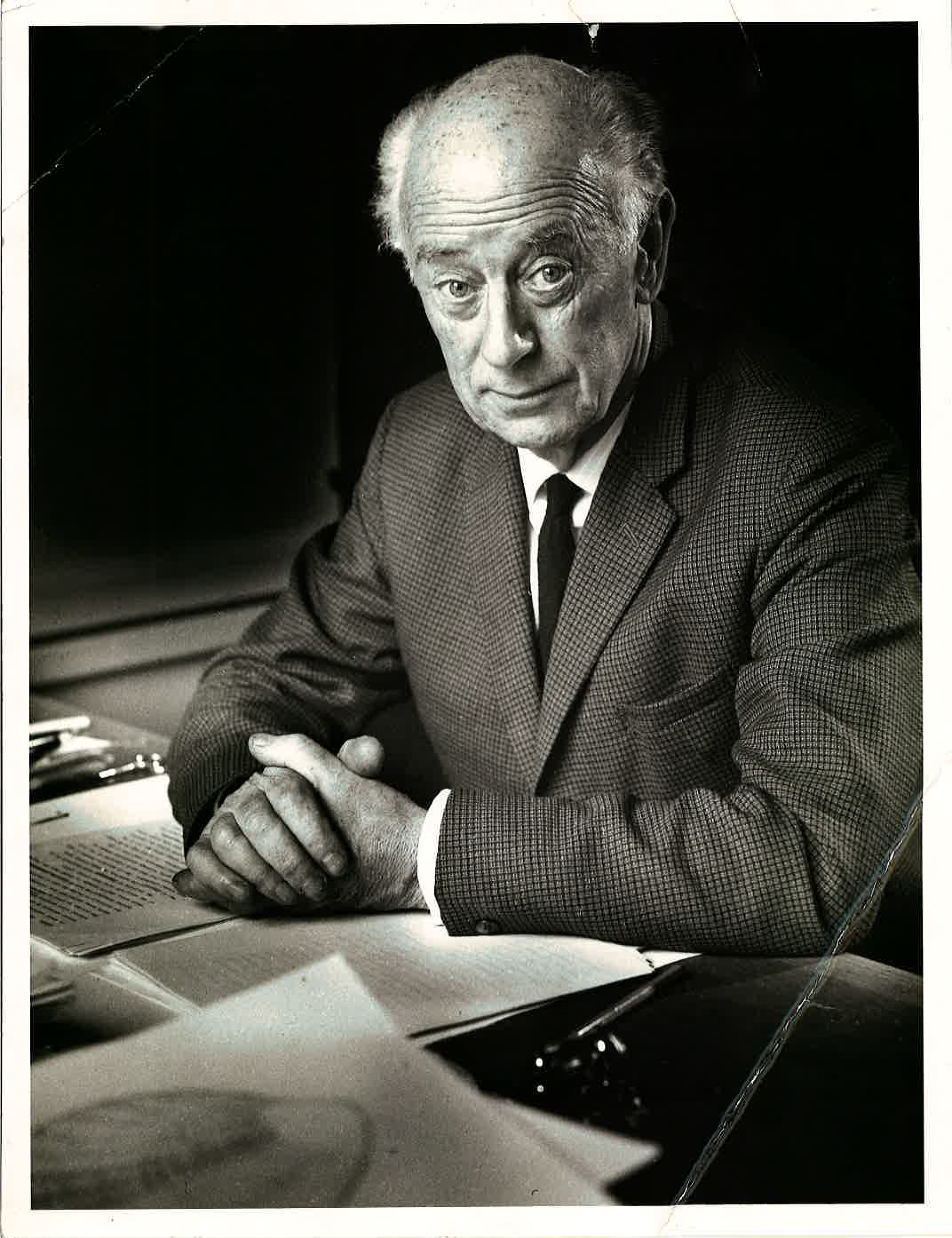

- Charles Maurice Yonge CBE PhD DSc FRS (1944)

Credit: ©University of Glasgow

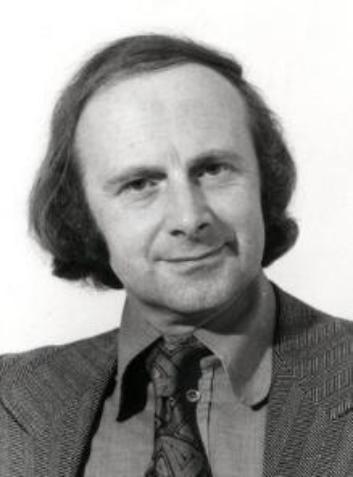

- David Richmond Newth BSc PhD (1965)

Credit: ©University of Glasgow

- Keith Vickerman PhD DSc FRSE FRS (1984-1998)

Credit: ©University of Glasgow

- 1998 - 2013 vacant

- FRS FRSE MAE PhD (2013 - Present)

Credit: ©University of Glasgow