| Please note that these pages are from our old (pre-2010) website; the presentation of these pages may now appear outdated and may not always comply with current accessibility guidelines. |

| Please note that these pages are from our old (pre-2010) website; the presentation of these pages may now appear outdated and may not always comply with current accessibility guidelines. |

| To complement the current Hunterian Museum exhibition Historic Bloomers: 300 Years of Botany at the University of Glasgow*, this month we feature one of the greatest scientific periodicals of all time, Curtis's Botanical Magazine. Begun in 1787, this journal is still being published to this day; it is the oldest periodical in existence featuring coloured plates, of which more than 11,000 have now been produced. The work of many acclaimed botanical artists, its volumes provide an exceptional pictorial record of floral fashions and plant introductions in Great Britain over the past two centuries. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The journal was founded by William Curtis (1746-1799). Although his passion for flora and fauna was evident from an early age, he was originally apprenticed as an apothecary. However, having moved from Hampshire to London in 1766 to practise this trade, his botanical interests prevailed and he abandoned his career to earn a precarious living by teaching and writing. His first publication was a pamphlet on collecting and preserving insects. In 1773, he was appointed as Demonstrator of Botany at the Chelsea physic garden. After leaving this post in 1777, he opened his own London Botanic Garden at Lambeth Marsh. He later moved the garden to a more salubrious site at Brompton. Admission to the garden and Curtis's lectures was by an annual subscription of one guinea; a share in plants and seeds could be had for a subscription of two guineas. |

| Curtis's first major publishing endeavour was his Flora Londinensis. Begun in 1774, this work aimed to illustrate the

plants growing around London. At the time, however, there was generally more

interest in showy exotic flowers than the native 'weeds' of London. Despite

its beautifully produced colour plates, it was a financial failure and never

completed. There was, however, a demand for an authoritative work on the

numerous new plants from overseas that gardening enthusiasts were trying to

grow at home. Curtis saw an opportunity to recoup some of the losses he had

incurred, and launched his Botanical Magazine. He initially used the

artists he had already employed for the Flora Londinensis, such as

James Sowerby (1757-1822) and William Kilburn (1745-1818), drawing on specimens

from his own botanical garden.

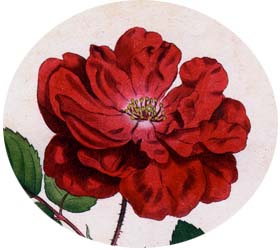

The artist who dominated the early years of the magazine, however, was Sydenham Teast Edwards (1768-1819). His talent was brought to the attention of Curtis who arranged for him to be trained in London as a botanical artist. He was only nineteen when his first plate was published in the Botanical Magazine in 1788. More than 1700 followed in the next 27 years - some published posthumously - to the virtual exclusion of other artists. Plate 279, shown to the right, is an example of his work. At first Edwards drew and engraved the plates himself, but from 1792 Francis Sansom took over the engraving. A few years before his death, Edwards left the Botanical Magazine to found his own Botanical register; his resentment had been incurred when 12 of his plates were erroneously attributed to Sowerby. |

|

|

|

The beautiful hand coloured plates are the chief glory of the magazine. The early examples are still largely bright and fresh, even after two hundred years. As Curtis states in the preface to the first issue, the plates were drawn 'always from the living plant, and coloured as near to nature, as the imperfection of colouring will admit'. With little chance to exert any artistic freedom, each artist had to draw the specimens exactly and accurately in order to create a scientifically authoritative work. Up to volume 70 the plates were created using copper etching, with watercolour being added to each copy. Considering that up to 3,000 copies of each issue (containing an average of 3 plates) were published in the magazine's early years, the impossibility of producing a standard uniformity in the colouring can be appreciated. Different colourists would produce varying results, while even the pigments used were not necessarily consistent in their quality. At one time, some 30 people were engaged in colouring the Botanical Magazine. Not only was this tedious and repetitive work, but low wages did not encourage high standards and there were inevitable fluctuations in care and accuracy. Incredibly, in spite of these problems, the magazine's plates were all hand coloured until as late as 1948 when a shortage of colourists forced the periodical to adopt photographic reproduction. |

| The choice of plants to be described was often influenced by the public's overwhelming appetite for the uncommon. At first, the plants selected were predominantly European, but the nineteenth century saw a huge increase in plants being sourced from further afield by intrepid plant collectors. David Douglas (1799-1834), for example, collected extensively in America on behalf of the Royal Horticultural Society. He travelled for eleven years, sending seeds and specimens back home at intervals; many of his plants flourished in England and were illustrated in the Botanical Magazine as they flowered. One of his finds, Diplopappus Incanus, is shown to the right; the accompanying text tells us that it is a native of California 'where it was discovered by Mr Douglas'. |

|

|

|

To start with, the accompanying textual description to each plate was fairly concise, consisting of: the plant's name, its place in the Linnean System of classification, generic and specific diagnoses, alternative names, the country of origin, the time of flowering, and notes on cultivation. The 'English' names cited were usually simply translations of the scientific name in Latin. Some of the plants were wrongly identified at the time, and they were also often figured by names that are now obsolete or obsolescent. For example, here the Winter Aconite's 'current' botanical name is cited as Helleborus hyemalis, but it has been more commonly known as Eranthis hyemalis for over a hundred years. This plant is now naturalised in Britain, but in 1787 it was much less common. Curtis died in 1799 when the magazine had reached its thirteenth volume. His friend John Sims (1749-1831), a botanist and physician, became the new editor. Sims renamed the publication Curtis's Botanical Magazine. During his time, increases in the cost of paper led to soaring prices so that by 1808 each issue cost three shillings and sixpence. As a result, circulation dropped to below 1,000. |

|

|

|

|

|

| As well as bringing in a new engraver, Joseph Swan of Glasgow, Hooker was innovative in introducing occasional double sized plates, and incorporating enlarged details into the illustrations in order to make points of specific differences more obvious. In fact, the magazine became decidedly more scientific and scholarly under his editorship. Floral dissections were included and the subjects generally became more wide ranging. In 1845, he made another change when lithography replaced copper engraving as the method of producing the plates. The inconsistent quality of their colour reproduction was a constant complaint of Hooker's; he felt that he could only achieve a 'fairly' accurate portrait of the plants. The main gripe of the publisher, however, was their high cost. One economic measure was to leave some parts of the plate uncoloured. Hooker died in 1865 at the age of 80. The curious plant above, Renanthera Lowii, is from the last volume for which he was responsible. The editorship was taken on by his son, Joseph Hooker, then Director at Kew. | |

|

|

Hooker had progressively delegated the task of illustrating the magazine to Walter Hood Fitch (1817-1892). A swift and industrious worker, he made his first contribution to Curtis's Botanical Magazine in October 1834. Over a 43 year period he published nearly 10,000 drawings. In Joseph Hooker's opinion, he was an 'incomparable botanical artist' with 'an unrivalled skill in seizing the natural character of a plant .. I don't think that Fitch could make a mistake in his perspective and outline, not even if he tried' (quoted by Blunt in Great flower books). He was responsible for the drawing of Thibaudia Sarcantha, shown to the left. His nephew John Nugent Fitch (1840-1927), meanwhile, produced some 2,500 lithographs for the magazine, including plate 7338 to the right. This was drawn by Matilda Smith, the cousin of Joseph Hooker, who was the principal artist of the magazine for over thirty years. |

|

|

|

Production of the magazine was plagued by economic difficulties throughout the nineteenth century. Sales had dropped to about 300 copies per month by 1848, and plagiarism in the form of unauthorised copying of the plates was another major problem. Despite this, the magazine struggled on unlike its many short lived rivals. In 1904, Joseph Hooker's son-in-law, Sir William Thiselton-Dyer, took over the editorship; he, too, was director at Kew. Like his predecessors, he quarrelled with the publishers over the standard of the hand coloured plates: these had to be produced for less than six pence each to make the venture economically viable. In 1921 the magazine was saved from extinction when H. J. Elwes bought the copyright and presented it to the Royal Horticultural Society which agreed to resume publication. There was a change of name to Kew Magazine in 1984, but in response to popular demand, the magazine reverted to its original name in 1995. Throughout the twentieth century, the magazine continued to employ the finest flower painters. Lilian Snelling (1879-1972) dominated the middle years of the century. She produced the last hand coloured plate for the magazine in 1948. She was succeeded as main illustrator by E. Margaret Stones. |

In publicising new and little known plants by means of accurate coloured plates and detailed descriptions, Curtis's Botanical Magazine has been an indispensible reference source for botanists and gardeners for over two hundred years. A complete run of the magazine forms the most comprehensive collection of plant-portraits in existence. The set in Special Collections (shelved at Sp Coll periodicals) ends in 1988; it includes index volumes and a volume of Curtis's Botanical Magazine dedications 1827-1927, published for the RHS by Quaritch. The core of this set is from the collection of George Arnott Walker-Arnott (1799-1868), Professor of Botany at Glasgow University. There is also a smaller run of the periodical bound up in order of flower species rather than in the order of publication. The library now subscribes to an on-line version of the magazine that provides full text access to issues from 1997 onwards. |

|

|

Wilfrid Blunt The art of botanical illustration London: 1950 Stack Botany B30 1950-B; Gavin D. R. Bridson Printmaking in the service of botany Pittsburgh: 1986 Level 11 Main Lib Fine Arts E953 1986-B; F. J. Chittenden 'History of Curtis's Botanical Magazine' in Curtis's Botanical Magazine Index London:1956 (pp. 251-269) Sp Coll Periodicals; Alice Margaret Coats The treasury of flowers London: 1975 Level 5 Main Lib Botany B30 1975-C; Ray Desmond Great Natural History Books and their Creators London: 2003; Sacheverell Sitwell and Wilfred Blunt Great flower books, 1700-1900; a bibliographical record of two centuries of finely illustrated flower books London: 1956 Sp Coll e7; Scottish Arts Council From Sowerby, Bauer, Hooker and Fitch: botanical illustrations 1800 to present day Edinburgh: 1975 Level 11 Main Lib Art Exhib B00957. *the Historic Bloomers temporary exhibition is no longer on display |

|

Return to main Special Collections

Exhibition Page Julie Gardham October 2004

|