Witchcraft and Demonology in: England

Scot, Reginald, 1538?-1599. Discoverie of witchcraft.

London, William Brome, 1584; quarto (Sp Coll Ferguson Ah-b.32, Sp Coll Ferguson Ap-d.15)

Scot’s was the first book in English to be devoted to the topic of witchcraft, apart from a few earlier English translations of continental works. This is a copy of the first edition and a rare book - largely due to the fact that James I (who called Scot’s views "damnable") ordered all copies to be destroyed in 1603.

Scot was convinced that those accused of witchcraft, and often their accusers, were not demoniacally possessed but mentally ill. He argued that a belief in witchcraft was "contrarie to reason, scripture and nature". "My greatest aduersaries" he wrote, "are young ignorance and old custome."

Gifford, George, d. 1620. A discourse of the subtill practises of deuilles by witches and sorcerers.

London, for Toby Cooke, 1587; quarto (Sp Coll Ferguson Ag-d.39)

The second major book on witchcraft in English.

Gifford, together with Scot, was one of the earliest opponents of the witchcraft delusion. He maintained that sickness and death - often attributed to witchcraft - could just as easily be explained by natural causes. He rejected spectral and hearsay evidence, and argued against conviction except when the evidence was conclusive.

A breife narration of the possession, dispossession, and repossession of William Somers: and of some proceedings against Mr. John Dorrell preacher ... Together with certaine depositions taken at Nottingham conerning the said matter.

[London?] 1598; quarto (Sp Coll Ferguson Ag-d.6)

John Dorrell was the only English exorcist of any real importance. His exorcism of William Somers of Nottingham in 1597 led to his downfall. In 1599 Dorrell and Somers were examined at Lambeth Palace and it was found that Somer’s possession by demons and Dorrell’s exorcism had been faked. Dorrell was declared an impostor and imprisoned for a year.

Although some suggest a London imprint, it has been suggested that this work may actually have been printed in Amsterdam.

Perkins, William, 1558-1602. A discourse of the damned art of witchcraft.

[Cambridge], Printed by Cantrel Legge, Printer to the Vniversitie of Cambridge, 1610; octavo (Sp Coll Ferguson Ah-e.29)

This book was first published posthumously in 1608. A second edition, of which this is a copy, came out in 1610.

Perkins’ work forms a reasoned defence of the belief in witchcraft. Though against convictions secured on the evidence of superstitious tests (e.g. swimming of witches), Perkins was in no doubt about the penalty, once guilt was proved. He believed that "this sinne of Witchcraft ought as sharply to be punished as in former times, and all Witches being thoroughly conuicted by the Magistrate, ought according to the Law of Moses to be put to death".

Potts, Thomas, fl. 1612-1618. The wonderfull discouerie of witches in the countie of Lancaster. With the ... triall of nineteen notorious witches, at the assizes ... at the Castle of Lancaster ... the seuenteenth of August last, 1612.

London, W. Stansby for John Barnes, 1613; quarto (Sp Coll Ferguson Ag-d.48)

The trial of the Pendle Forest witches of Lancashire in 1612 was the largest mass trial of suspected witches to that date. Of the nineteen persons tried ten were hanged, one was sentenced to be put in the pillory, and the other eight were acquitted.

This pamphlet is of a semi-official nature. Its compiler, Thomas Potts, was clerk of the court of Lancaster, and it also had the approval of the judge, Sir Edward Bromley.

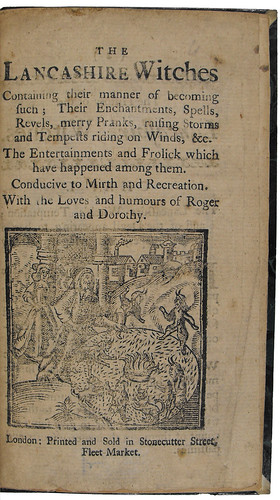

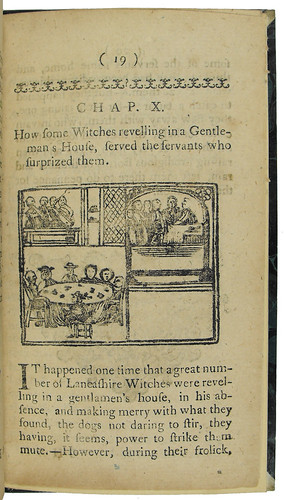

The Lancashire witches containing their manner of becoming such; their enchantments, spells, revels, merry pranks.

London, n.d.; octavo (Sp Coll Ferguson Af-g.20)

This chapbook, divided into twelve short chapters, gives a rather more light-hearted description of the Lancashire witches. Writing about witches in general, the author says: "But the Lancashire witches, we see divert themselves in merriment, and are therefore found to be more suitable than the rest".

The wonderful discoueries of the witchcrafts of Margaret and Phillip Flower, daughters of Ioan Flower neere Beuer Castle; executed at Lincolne ... 1618. Who were ... condemned ... for confessing themsleves actors in the destruction of Henry Lord Rosse, with their damnable practises against others the children of ... Francis Earle of Rutland.

London, G.Eld for I Barnes, 1619; quarto (Sp Coll Ferguson Ag-d.5)

This pamphlet illustrates some of the practices attributed to witches.

Margaret Flower and her sister Phillipa (called "Phillip" in the pamphlet) were servants of the Earl of Rutland. In revenge for her dismissal, Margaret Flower stole a glove belonging to Lord Rosse, Rutland’s heir, and gave it to her mother, who stroked her cat called Rutterkin with it, dipped it in boiling water, pricked it, and buried it. Later Lord Rosse fell ill and died.

The pamphlet is illustrated by a woodcut which shows a contemporary conception of three witches with their familiars (i.e. demons in the shape of small animals whose function was to advise and assist witches).

Doctor Lamb’s darling: or, strange and terrible news from Salisbury; being a true ... relation of the ... contract and engagement made between the Devil, and Mistris Anne Bodenham.

London, for G. Horton, 1653; quarto (Sp Coll Ferguson Ag-d.59)

In 1653 Anne Bodenham, at one time servant to John Lambe, was convicted of witchcraft and sent to the scaffold at Salisbury.

The pamphlet states that she could transform herself into the shape of a "Mastive Dog, a black Lyon, a white Bear, a Wolf, a Monkey" etc.

A most certain, strange and true discovery of a witch. Being taken by some of the Parliament forces, as she wa standing on a small planck board and sayling on it over the river of Newbury ...

[London], John Hammond, 1643; quarto (Sp Coll Ferguson Al-x.57)

The pamphlet, written during the Civil War, describes how the witch was fired at by soldiers of the army of the Earl of Essex, "but with a deriding and loud laughter ... she caught their bullets in her hands and chew’d them". Eventually however one of the soldiers succeeded in shooting her.

The title page of the pamphlet bears a woodcut, which shows the witch sailing on her plank on the river.

Bound with eight other seventeenth century tracts on witchcraft.

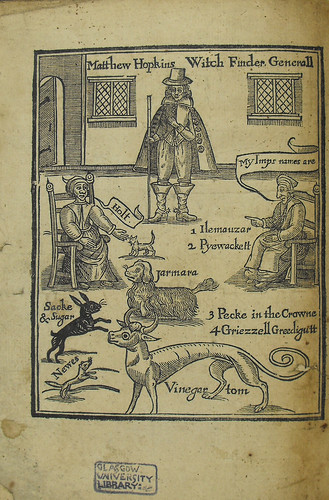

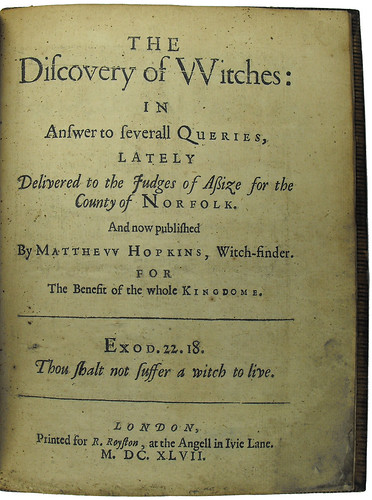

Hopkins, Matthew, d. 1647. The discovery of witches.

London, for R. Royston, 1647; quarto (Sp Coll Ferguson Ag-d.47)

Matthew Hopkins, England’s most notorious witch-hunter, centred his activities in Essex and the surrounding counties. Despite his short career - he started only in 1645 and died in 1647 - it has been estimated he managed to condemn over 200 people to death. At first he was received enthusiastically, but by 1646 his influence was declining, partly due to the exposure of his methods in John Geule’s Select cases of conscience touching witches, 1646.

Filmer, Robert, Sir, d. 1653. An advertissement to the jury-men of England, touching witches.

London, I.G. for Richard Royston, 1653; quarto (Sp Coll Ferguson Ag-f.44)

Sir Robert Filmer was an important political writer of the mid-seventeenth century.

In this, his only publication on witchcraft, Filmer recommended careful thought and moderation in witch trials. He dismissed the eighteen proofs of witchcraft put forward by William Perkins half a century earlier in his Discourse on the damned art of witchcraft. Filmer’s pamphlet was published anonymously.

Webster, John, 1610-1682. The displaying of supposed witchcraft.

London, printed by J.M., 1677; folio (Sp Coll Ferguson Ag-x.12, Sp Coll Ferguson Ah-y.3)

Writing in opposition to the views of Meric Casaubon and Joseph Glanvill, both believers in the Satanic origin of witchcraft, Webster acknowledged the existence of witches and their ability to work evil, but only through "meer natural means" and not by the aid of the Devil.

This is a large paper copy, bound in red morocco, with the monogram of Charles II stamped in gold in the four corners of each cover and on the spine.

Glanvill, Joseph, 1636-1680. Saducismus triumphatus: or, full and plain evidence concerning witches and apparitions.

London, for J. Collins and S. Lownds, 1681; octavo (Sp Coll Veitch Eg6-d.14)

The author was held "to have put the belief in apparitions and witchcraft on an unshakable basis of science and philosophy". - G.L. Kittredge, Witchcraft in Old and New England.

Glanvill, an Oxford man, was a Fellow of the Royal Society and Chaplain in Ordinary to Charles II.

A true and impartial relation of the information against three witches, viz. Temperance Lloyd, Mary Trembles, and Susanna Edwards. Who were ... convicted at the assizes holden ... at the Castle of Exon, Aug. 14, 1682.

London, by Freeman Collins, sold by T. Benskin, and C. Yeo in Exon., 1682; quarto (Sp Coll Ferguson Ag-c.4, Sp Coll Ferguson Ag-d.36, Sp Coll Ferguson Al-x.57)

In spite of the writings of sceptics, popular feeling was very much against witches. The trial of the three women named in this pamphlet engendered so much local uproar and fury that Roger North, Attorney-General under James II, could write in his autobiography: "A less zeal in a city or kingdom hath been the overture of defection and revolution, and if these women had been acquitted, it was thought that the country people would have committed some disorder".

A tryal of witches, at the assizes held at Bury St. Edmunds ... on the tenth day of March, 1664.

London, Sir William Shrewsbery, 1682; octavo (Sp Coll Ferguson Af-g.6, Sp Coll Ferguson Al-x.57)

Charges of sorcery and the bewitching of children, made against Rose Cullender and Amy Duny, two widows of Lowestoft, resulted in their trial at Bury St. Edmunds. They were found guilty and hanged.

This trial was important not only because of the prominence of the judge, Sir Matthew Hale, a lawyer of high repute, but also because the printed account of the proceedings was circulated in New England. At the Salem witch trials in 1692 this tract was consulted by the judges, who were in need of precedents for witch trial procedure.

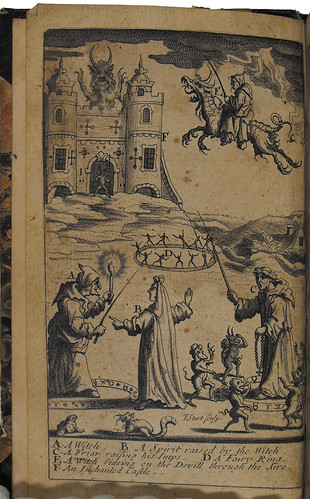

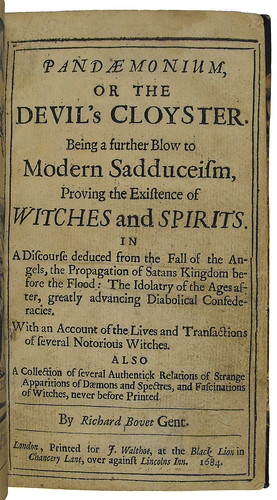

Bovet, Richard, b. ca. 1641. Pandaemonium, or the devil’s cloyster.

London, for J. Walthoe, 1684; duodecimo (Sp Coll Ferguson Ap-y.76)

The first part of this work is largely culled from two earlier writers, Glanvill and Daniel Brevint, Dean of Lincoln Cathedral. The second part consists of fifteen ghost stories.

The evil spirit cast-out. Being a true relation of the manner of performing the famous operation or cure, on the maiden gentlewomen, whose body was possessed with an evil spirit.

London, E. Golding, 1691; octavo (Sp Coll Ferguson Ag-d.29)

An account of an exorcism. The afflicted woman was given "the distilled waters of rosemary, angelica, and marigolds" and prayers were said frequently. The combination of the two was eventually successful in expelling the demon.

The tryal of Richard Hathaway, upon an information for being a cheat and impostor, for endeavouring to take away the life of Sarah Morduck, for being a witch, at Surrey assizes.

London, for Issac Cleave, 1702; folio (Sp Coll Ferguson Ah-y.4)

Of interest because it provides evidence that some accusations of witchcraft were based on fraud.

Sarah Morduck, accused by Hathaway of bewitching him, was acquitted (though the verdict was extremely unpopular). Hathaway at his own trial was exposed as a fraud and perjurer. Sir John Holt, the judge at Hathaway’s trial, was outstanding among his contemporaries for his impartiality and for his discouragement of convictions for witchcraft.

Bragge, Francis, b. 1690. A full and impartial account of the discovery of sorcery and witchcraft, practis’d by Jane Wenham of Walkerne in Hertfordshire. The second edition.

London, for E. Curll, 1712; octavo (Sp Coll Ferguson Ag-d.27)

The trial of Jane Wenham is important because she was the last person to be condemned to death in England for witchcraft. The sentence was never carried out. Sir John Powell, the judge at the trial, obtained a royal pardon for her.

The trial resulted in the publication of numerous pamphlets, both for and against Jane Wenham. This tract by Francis Bragge, one of the clergymen involved at the trial, stated the case against her.

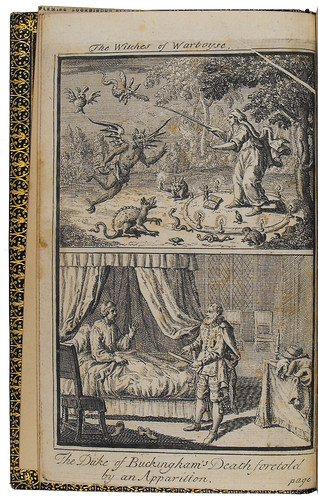

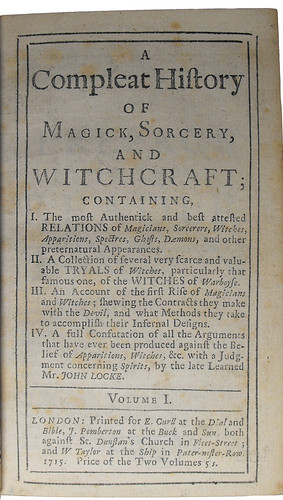

Boulton, Richard, b. 1676 or 7. A compleat history of magick, sorcery, and witchcraft.

London, for E. Curll et al., 1715-16; duodecimo (Sp Coll Ferguson Ap-y.84-85, Sp Coll Ferguson Al-b.7-8)

The last serious attempt in English to defend the belief in witchcraft and magic.

Boulton, a physician, was educated at Oxford and lived for a time in Chester.

Hutchinson, Francis, 1661-1739. An historical essay concerning witchcraft.

London, for R. Knaplock and D. Midwinter, 1718; octavo (Sp Coll Ferguson Al-a.49, Sp Coll BE6-d.14)

Wallace Notestein, in his History of witchcraft in England from 1558 to 1718, wrote that Hutchinson’s work "levelled a final and deadly blow at the dying superstition. Few men of intelligence dared after that avow any belief in the reality of witchcraft ...".

Hutchinson was made Bishop of Down and Connor in 1720. Prior to that he had been vicar at Bury St. Edmunds, the scene of two series of witch trials in the mid-seventeenth century.

Back to see books on Witchcraft and Demonology in France and Italy

Forward to see books on Witchcraft and Demonology in Scotland