What does Electricity Market Reform mean for Scotland?

Published: 20 January 2025

Commentary

Dr Nicholas Harrington, from the UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (CaCHE), examines the UK government's recent consultation on electricity market reform, the options that are still under consideration such as zonal pricing, and the impact those reform options might have on consumers.

It is widely acknowledged that the UK’s electricity market is unfit for purpose. The UK has the most expensive electricity in Europe, despite having one of the highest levels of renewables generation (51.6% of total generation). This is somewhat counterintuitive.

How can it be that as more and more electricity is generated with a zero input cost (solar, wind, etc.), consumers pay ever higher prices?

And what of all those renewables projects on government-backed CfDs (Contracts for Difference)? Aren’t consumers supposed to see a ‘payback’ benefit through reduced energy bills when those generators return excess profits to the Low Carbon Contracts Company (LCCC)?

The answer to these riddles is that (A) the paybacks the LCCC receive go to electricity suppliers, (not consumers) while suppliers are under no legal obligation to pass those returns onto their customers (despite charging customers directly for maintaining the CfD scheme in the first place); and, (B) the electricity market operates in such a way that the most expensive unit of electricity required to meet demand at any given time, sets the price for all the electricity traded in that period. In practice, this means high-cost gas-fired power plants set the electricity price 98% of the time, rather than there being a proportional price effect from the high share of renewables generated electricity in the mix (as one might expect).

The first issue is a regulatory problem, the second is a structural dilemma.

Critically, the UK government (through the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero – DESNZ) has been consulting on reforming the UK’s electricity market for the last two years – ostensibly to investigate and treat precisely these kinds of dysfunctions. This Review of Electricity Market Arrangements (known as REMA), has gone through two consultations and is now approaching its final phase.

Let’s examine what reforms (of those that remain on the table) might lower the consumer cost of electricity, and how these might impact Scotland, in particular.

To date, the headline outcomes of REMA are:

- Retain short-run marginal pricing in the wholesale market

- Rejected Split Market or Green Power Pool

- Still considering zonal pricing

Reflecting on these in order:

- Retaining short-run marginal pricing (the structural feature that permits gas to set the price of electricity) suggests wholesale prices will remain artificially high for the foreseeable future since total demand is rarely met by renewables-generated electricity across the UK at any given time.

- Rejecting a Split Market or Green Power Pool (two proposals that suggest renewables generated electricity be traded separately from the more expensive gas- and nuclear-generated electricity) eliminates two powerful ways of ensuring (at least a certain proportion of) consumers receive the benefit of low-cost renewables generated electricity.

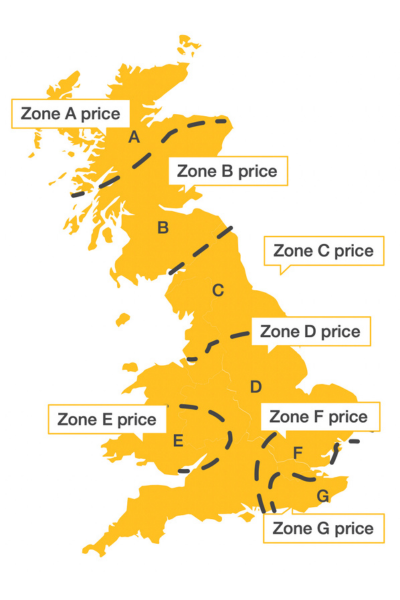

- Considering zonal pricing suggests DESNZ is weighing the merits of splitting the UK into a (as yet undetermined) number of separate markets (zones) that would trade their electricity based on what they generate internally and how much might need to be imported from outside their zone.

Let’s explore zonal pricing a little further.

Independent analysts have found that if the UK moved to zonal pricing (if the electricity market was divided into zones and Scotland represented a unique zone) the price of electricity in Scotland would fall considerably, an argument also made by Chief Executive of renewables-focused Octopus Energy Greg Jackson over the weekend. Interestingly, in recent months, a number of large energy companies have released their own research arguing that a move to zonal pricing will not benefit consumers and may instead harm investment in renewables.

Figure 1. Illustration of Zonal Pricing Map of UK (example only)

My research suggests that under a zonal pricing structure, the price of electricity in Scotland could fall considerably, but that hinges on whether the Scottish government invests in the storage and transmission infrastructure necessary to get the renewables generated electricity where it is needed and save it for use when the wind isn’t blowing as hard. Without these ‘system flexibility’ investments, there will still be certain places that can’t access cheap renewables electricity and times of the day when wind farms don’t generate enough to meet demand. That situation describes what we have right now – more expensive imported or gas-generated electricity setting the price consumers pay.

Recently, I attended the First Scottish Forum on Future Electricity Markets in Edinburgh. Given the emphasis the DESNZ representatives placed on ‘investment risk,’ ‘market uncertainty’ and ‘implementation complexity’ when discussing zonal pricing (combined with the obvious pushback they are getting from the large energy suppliers), I have a sneaking suspicion zonal pricing will be rejected when all is said and done with REMA.

If my intuition is correct, this two-year electricity market review period will, therefore, have revealed a profound status quo bias in government and represent an unfortunate once-in-a-generation missed opportunity to improve the situation for consumers UK-wide and Scots, in particular.

This blog was originally posted on the Centre for Public Policy website.

First published: 20 January 2025